Asia’s economic reordering has so far been told through its edges. Japan's world-class profits conceal capital inefficiency. South Korea's industrial excellence is constrained by export dependence and geopolitical pressure. Vietnam's ascent reflects high-growth optimism colliding with institutional fragility. Yet each of these economies ultimately orbits the same centre of gravity. China is not merely another case study in Asia’s structural shift; it is the system against which the region calibrates itself. And today, China’s problem is no longer growth, but credibility.

For decades, Beijing relied on scale to overcome inefficiency. High savings, state-directed investment, and export competitiveness compensated for weak domestic consumption and misallocated capital. That model delivered extraordinary expansion.

But as growth slows, the very mechanisms that once powered China’s rise are now constraining its ability to adapt. The result is an economy that remains industrially formidable yet increasingly unable to generate confidence among consumers, private firms, and global capital.

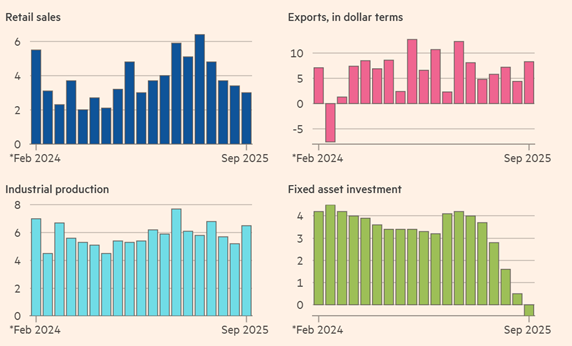

On paper, China continues to defy pessimism. Industrial output remains robust, expanding close to 5 per cent year-on-year, supported by resilient exports that have risen more than 8 per cent annually despite collapsing shipments to the US [Financial Times]. Manufacturing capacity has not vanished; it has been redirected, particularly towards south-east Asia and other emerging markets. This helps explain why Vietnam’s manufacturing inflows and export gains cannot be understood in isolation from China’s own industrial overflow.

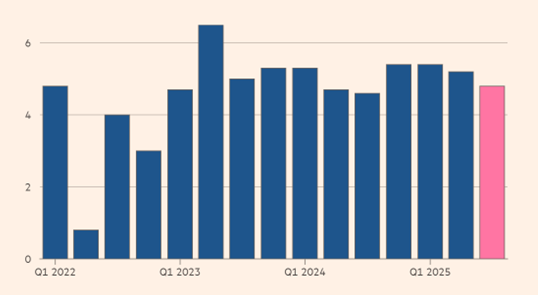

Yet beneath this resilience lies a widening imbalance. Official GDP growth has slowed to below 5 per cent, the weakest pace in a year, missing Beijing’s longer-term comfort zone even as policymakers continue to target “around 5 per cent” expansion.

More troubling is the composition of that growth. Consumption remains anaemic, retail sales growth has slowed to barely above 1 per cent, and consumer prices are falling, signalling persistent deflationary pressure. Unlike Japan, where households save despite stable incomes, China’s consumers are adopting more cautious spending behaviours amid uncertainty. And unlike South Korea, where exports are constrained by geopolitics, China’s exports remain competitive but increasingly distortive, masking weakness elsewhere in the economy [Business Standard].

Nowhere is the confidence deficit clearer than in property. Despite repeated mortgage rate cuts and policy support, new home prices continue to fall, with monthly declines accelerating to their steepest pace in nearly a year. Property investment has contracted by close to 14 per cent year-on-year, eroding a pillar that once absorbed household savings, local government revenue, and construction employment.

This matters not simply because the property sector was large, but because it functioned as China’s informal balance sheet, the property downturn has effects far beyond construction activity. As prices fall, households feel poorer and defer spending, developers remain financially constrained, and local governments lose a critical source of fiscal revenue. This interaction increasingly resembles a balance-sheet recession. High savings coexist with weak spending, while policy stimulus struggles to gain traction because the core problem is not access to liquidity but a collapse in confidence. Japan faced a similar reckoning in the 1990s. The difference is that China is confronting it at a much lower income level and with far less transparency in its national accounts, making the adjustment both economically and politically harder to manage.

If consumption is weak, investment should compensate. Yet fixed asset investment continues to contract, falling more than 2.5 per cent year-on-year, with single-month declines running into double digits. Beijing’s own diagnosis has become unusually blunt. President Xi has openly criticised “reckless” and “wasteful” government spending, targeting inflated development zones, redundant high-tech projects, and “fake construction starts” designed to embellish growth figures.

This marks a striking inflection. For years, state-led investment was China’s stabiliser of last resort. Now, it is being recast as a source of distortion, contributing to excess capacity, vicious price competition, and what policymakers call “involution”: growth that destroys profitability rather than creating value [Financial Times]. The automotive sector illustrates the risk. Capacity has surged on the back of subsidies and local government support, driving prices down and margins with them. Regulators are now threatening crackdowns on unfair pricing, underscoring how state-driven expansion can undermine the very industries it seeks to promote.

Here, the contrast with Japan is instructive. Japanese firms hoard cash rather than misallocate it. Chinese local governments invest aggressively, but increasingly without credible demand to justify it. Both systems suppress returns on capital, but through opposite behaviours.

China’s export strength has become both a buffer and a liability. Shipments continue to rise globally, even as trade with the US declines and exports of strategic goods such as rare earth magnets fall sharply to American buyers. This has supported headline growth, but it has also intensified global tensions, with trading partners accusing Beijing of exporting deflation rather than stimulating domestic demand. The IMF has echoed this concern, urging stronger measures to reflate the economy and boost consumption. While Chinese leadership has rhetorically embraced domestic demand as a “strategic move”, policy priorities remain tilted towards high-tech production and industrial upgrading.

The next five-year plan continues to emphasise investment over household income growth, reinforcing doubts about whether consumption will ever play the role policymakers assign to it [Investing]. South Korea faces export dependence because it must. China increasingly chooses it because it distrusts its own domestic engine.

China’s predicament is not one of capacity or capability. It remains the world’s most complete industrial economy, with scale, skills, and infrastructure unmatched by any peer. But growth systems ultimately rest on belief. Consumers must believe their incomes are secure. Private firms must believe investment will be rewarded. Global investors must believe the rules are predictable.

That belief is now fragile. High savings no longer translate into high confidence. The state capital crowds out private initiatives. Data opacity, from the absence of full GDP expenditure breakdowns to the withdrawal of detailed investment statistics, compounds uncertainty rather than alleviating it.

In contrast, Vietnam attracts optimism despite its institutional gaps. South Korea still commands trust in its firms, if not its macro stability. Japan retains credibility even as it struggles with inefficiency. China, uniquely, risks possessing the most scale with the least confidence.

To conclude, Asia’s leading economies reveal different responses to the same structural pressures. Japan hoards capital instead of deploying it. South Korea exports risk while struggling to diversify demand. Vietnam imports optimism while racing to build institutions. China suppresses confidence through overinvestment, opacity, and a reluctance to rebalance decisively toward households. This is why China’s slowdown matters beyond its borders. As the region’s anchor, its choices shape trade flows, capital allocation, and policy constraints across Asia. If Beijing continues to prioritise production over consumption, scale over credibility, it may preserve growth rates in the short term while eroding the foundations of durable expansion. China’s challenge is no longer to grow faster. It is to convince its own economy that growth is worth believing in again. Until that confidence is restored, Asia’s reordering will continue to unfold not around China’s strength, but around its hesitation.