Digital art was first thrust into the spotlight during the NFT boom of 2021, when speculative excitement drove eye-watering sales and headlines of million-dollar Jpegs. However, as quickly as it rose, the frenzy faded, leaving behind questions over the longevity of blockchain in the art world.

Although the hype surrounding million-dollar Jpegs has largely disappeared, experimentation with the tokenisation of physical art has continued. Increasingly, galleries and traditional auction houses are experimenting with the tokenisation of physical works of art. This involves splitting a single artwork into thousands of digital shares, theoretically enabling fractional ownership for the average person and making fine art appear as investable as stocks.

While enthusiasm is growing around the possibility of democratising access to this historically exclusive market, critics remain sceptical over whether tokenisation can truly deliver on its promises.

They argue that a genuine store of value in art has always relied on factors such as provenance, scarcity, and cultural relevance, which are all qualities that cannot be guaranteed by technology alone. As interest in the space from regulators and investors grows, art is seemingly becoming a test case for how tokenisation might transform the ownership of real-world assets more widely.

Whether tokenised art proves to be a lasting financial innovation or merely another passing experiment of its time will be crucial in determining the future of blockchain’s broader relevance beyond the art world as well.

In order to tokenise a piece of art, the artwork itself must be legally structured as an investable asset. The artwork is appraised, with a valuation decided by art specialists. Once a mutually agreed-upon valuation has been reached, digital tokens are then issued to represent shares in the work.

For example, a gallery might choose to tokenise a £5 million painting by issuing 50,000 tokens at £100 each, allowing individuals to acquire small shares in the work. The key difference is that instead of taking a canvas home, as traditionally would be the case, investors receive only financial exposure to the underlying work rather than physical possession or display rights.

Any potential return comes from appreciation in the work’s price or the resale of tokens, and in some cases from revenue if the piece is loaned or exhibited. Due to this, tokenised shares are often categorised more closely to traditional securities than to previous NFT collectibles.

A common argument from those in favour of art tokenisation is that it allows for broader participation in an asset class that has traditionally been completely out of reach for the average retail investor.

Fractional ownership lowers the financial threshold for entry, enabling individuals to access works that would typically only be available to museums, private collectors, or wealth managers.

Sygnum, the Swiss digital asset bank behind the tokenisation of Picasso’s Fillette au béret, also argues that it could bring greater transparency to the pricing of artworks, where valuations tend to rely more on reputation than on concrete data. For example, a painting sold privately in 2019 might not resurface until 2026, with its interim value decided largely by a handful of auction results.

Tokenised shares, by contrast, trade frequently on digital platforms, creating a transparent record of buying and selling activity. Therefore, instead of depending on twice-yearly auction results or private valuations, artwork pricing should now be able to reflect ongoing investor demand more closely.

Younger investors, particularly in Asia, are driving the most growth in the space. In South Korea, for example, platforms such as TESSA report that over half their users are in their 20s and 30s and have invested across multiple Banksy works, with many young people now treating art as part of a broader basket of alternative assets (Fine Art Group Report).

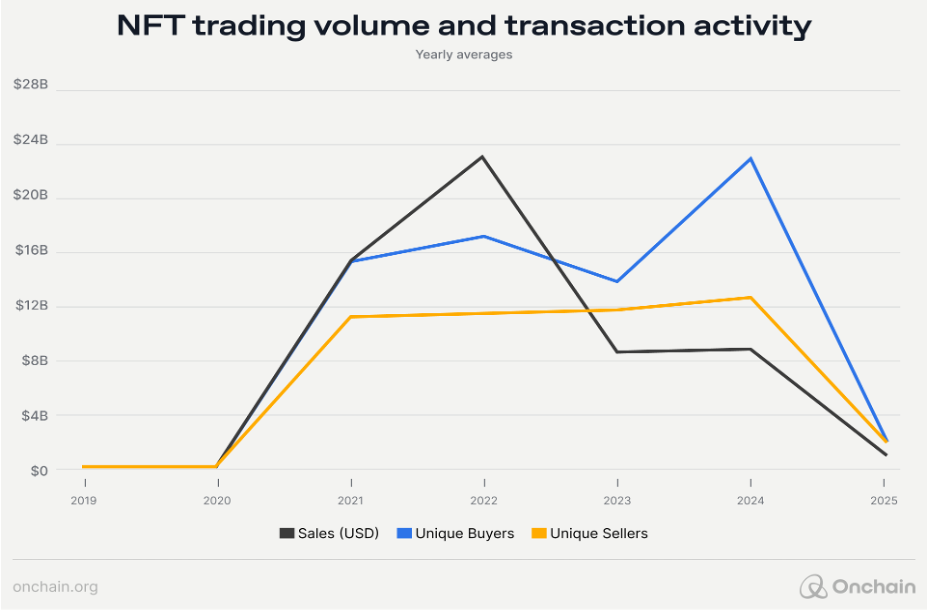

In many ways, set against the NFT crash, the success that tokenised art has enjoyed seems rather unexpected. The art NFT market has fallen from roughly $2.9 billion at its 2021 peak to around $24 million by early 2025 (NFT Art’s Shocking Collapse). However, instead of turning away from blockchain altogether, it seems the collapse instead led investors to turn their attention to real world asset tokenisation, where regulators have shown greater willingness to engage.

Europe’s MiCA legislation came into force in 2024, which established clear disclosure and custody requirements for asset referenced tokens. In the US, the SEC has signalled that fractional art offerings may fall under securities law if investors expect profits from the venture, a significant step forward in bringing tokenised artworks closer to regulated investment products than the NFTs of the past.

Undoubtedly, evidence of momentum in tokenised art is emerging across both the institutional and experimental ends of the market. Sotheby’s first launched its Metaverse platform in late 2021 and later introduced on chain secondary trading. Since then, the auction house has handled more than $120 million in digital art sales.

Christie’s followed a year later, releasing its own blockchain settled platform, proving another clear indicator that major auction houses view such digital infrastructure as a crucial part of their strategy going forward.

Alongside this, global online art investment marketplaces such as Masterworks have also emerged. Masterworks has securitised over $800 million of works by artists including Banksy and Basquiat, and now claims more than 800,000 users, a scale that dwarfs traditional art fund participation.

However, for some in the industry, this trend is nothing new. In the 1980s and 1990s, art investment funds attempted to democratise access through pooled structures. According to them, tokenisation appears to represent a more technologically sophisticated iteration of the same ambition, however now under a far more cautious regulatory gaze.

Yet even as adoption gathers pace, tokenisation continues to attract scepticism. The main concern seems to be less about the technology itself and more about what it cannot replicate. Value in art will always be heavily dependent on networks, taste and institutional endorsement.

Whilst blockchain can indicate who owns 0.02% of a painting, it cannot replicate the ecosystem that gives art value in the first place. For example, a specific dealer who places a work with a museum or a collector whose name strengthens a provenance line can materially lift a valuation.

You may think that those factors should eventually be reflected in token prices. However, in practice, the relationship is far looser. Thin liquidity, retail driven trading and the faster tempo of crypto markets mean that recognition in the institutional art world does not always translate into the fractional markets. This could easily leave investors holding exposure to a prestigious work that, in token form, struggles to attract buyers or reflect momentum in the physical market.

Another issue is regulatory uncertainty. Questions around disclosure, custody and investor protection are only beginning to be tested. Platforms offering tokens must deal with anti money laundering requirements, custody rules and questions around who bears responsibility if valuations collapse. This leaves many platforms straddling an awkward middle ground between retail friendly marketing and the obligations associated with regulated investment products.

Furthermore, liquidity is also a persistent challenge, and one that the industry is already all too aware of. Traditional art tends to sell infrequently, often through networks and relationships built over decades. For digital trading platforms to succeed, they rely on a consistent stream of buyers. If enthusiasm fades, secondary markets can freeze very quickly, leaving investors holding shares in an asset they cannot exit without accepting steep losses.

Ultimately, the deeper fear, even voiced by certain supporters, is that tokenisation risks recreating the very same incentives of the NFT boom. People may trade tokens, not engage with art, and the promised ‘democratisation’ will never materialise. The question is less whether blockchain can fractionalise a painting, which has already been proven possible, and more so whether doing so produces anything other than volatility repackaged as ‘access’.

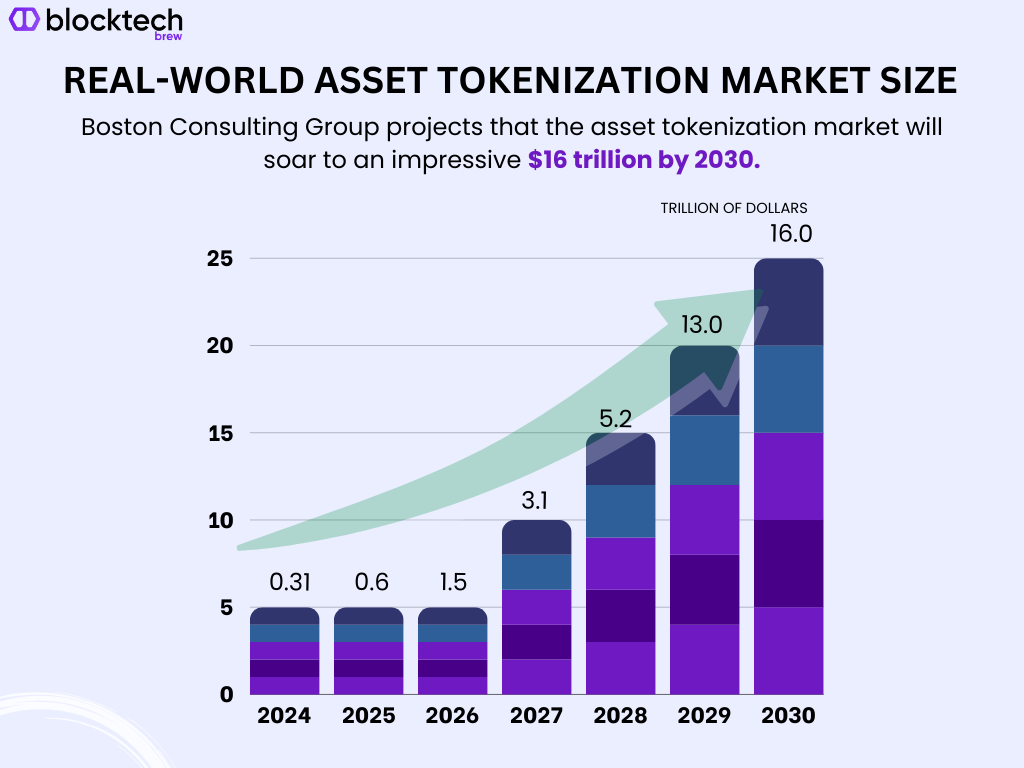

For investors, the art world has become an improbable test case for real world asset tokenisation. At the same time, it is also a hugely demanding one. Unlike property or private credit, art offers no cash flows and limited data driven valuation measures.

If tokenisation can establish credibility in this niche market built on trust and taste, its prospects in other asset classes like private real estate, music rights and luxury goods will look materially stronger. If it cannot, the sector will surely be remembered as a sophisticated re run of the NFT boom.

Either way, the outcome of the art tokenisation experiment will be extremely useful in determining whether blockchain becomes part of the established financial plumbing or remains a niche experiment at the fringes of the market.