On 23 September 2022, Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng unveiled an ambitious package they believed would return growth to a sluggish UK economy. The plan was simple: cut taxes, increase energy subsidies, and reduce regulatory oversight for investment and production. Disregarding foundational economic concepts, a scrapping of the additional 45% tax rate, a reduction in the basic tax rate to 19%, and a reversal of corporation tax hikes would seem beneficial for millions across the country. However, given the macroeconomic backdrop of the UK at the time, these proposals were unfeasible at best, and the harshest critics would say moronic.

According to the Commons Library, the tax cuts outlined in the mini budget would have reduced Treasury revenues by around £45 billion per year by 2026-27. When combined with the Government’s Energy Price Guarantee, the result was an additional borrowing requirement of £72 billion in the 2022-23 fiscal year alone, as outlined by NatWest’s Head of Global Economics.

For context, the Truss Government had inherited an economy where average inflation throughout the year was 9.2%, a figure only matched in two years since the early 1980s. With inflation running hot and stock in the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) swollen to nearly £900 billion at the time, the central bank had little choice but to embark on a monetary tightening mission. This involved base rate hikes and quantitative tightening as essential tools to combat inflation and a bloated balance sheet. By September 2022, the base rate had risen to 2.25% and the central bank had outlined its approach to gilt sales, setting an £80 billion stock reduction target that included both maturities and sales for the 12 months from October 2022.

As the IMF highlight, “It is important that fiscal policy does not work at cross purposes to monetary policy,” a statement that Truss and Kwarteng seemed to outright ignore. Goals of lower inflation and controlled borrowing by the BofE were contrasted by targets of artificially fuelled growth by Truss and Kwarteng. Can you see the issue here?Unsurprisingly, markets took the news, shall we say … horrendously. On announcement day, GBP/USD rates plunged circa 3% to around £1/$1.09, a 37 year low. A weak pound heightened the cost of importing and, if maintained, would inevitably have fuelled inflation further. Mortgage rates soared and Nationwide reported that house prices had fallen by as much as 0.9% in October 2022.

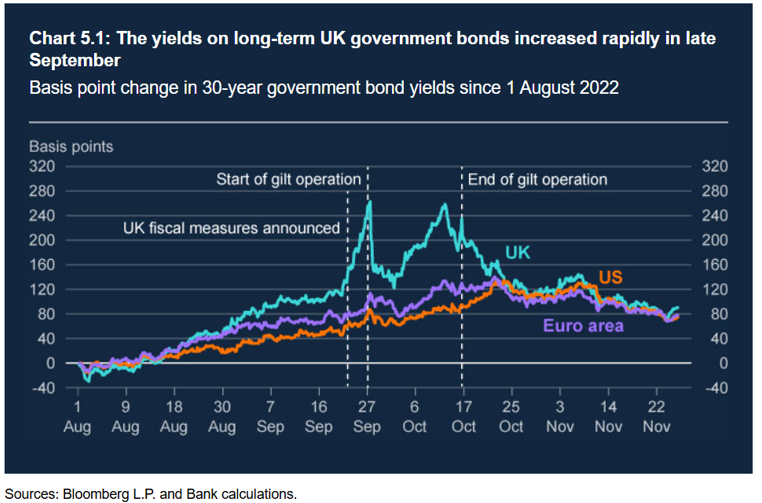

If you have followed my previous articles around why gilt yields remain elevated in the current environment, it will come as no surprise that UK gilts also saw their largest one day jump since 1991 following the budget. Amidst the sell off in gilt markets, pension funds faced potential collapse, forcing the Bank of England to backtrack on their objectives and buy long dated gilts back off the market. Defined benefit schemes and liability driven investment funds were effectively forced into selling £37 billion worth of gilts in the period 23 September 2022 to 14 October 2022 to meet collateral requirements. In the same period, the BofE stepped in to purchase £19.3 billion worth of gilts in an attempt to stabilise yields and “reduce risks from contagion to credit conditions for UK households and businesses.”

Credit rating agency Moody’s stated that large unfunded tax cuts would lead to rising borrowing costs. Although they did not change the UK’s credit rating, they starkly warned that the unfunded stimulus would prompt more aggressive monetary tightening and hamper growth in the medium term, contradicting Truss’s objectives.At first, Truss and Kwarteng doubled down, branding the budget as “absolutely essential” to reset the debate around growth and flat out refusing to reverse the measures taken. However, the damage was already done, a gilt market in turmoil, a pound so weak that currency desks were checking it for vital signs of life, and ultimately, two Conservative politicians left with very red faces.

Within weeks, the government had fallen apart and newly appointed Chancellor Jeremy Hunt had reversed the majority of the planned tax cuts, strengthening the pound and returning some form of normality to gilt yields. As Citadel’s CEO Ken Griffin observed, it was “the first time we’ve seen a major developed market…lose confidence from investors.”

On the 21st of November 2025, in a move with very similar objectives to the mini budget, Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi received approval for a stimulus package totalling $135.5 billion. The package, involving cash handouts, tax cuts, energy subsidies and domestic investment, was crafted to spur economic growth and protect households from the rising cost of living. It is reported that the stimulus was based on three pillars and is the largest such package since the Covid-19 pandemic.

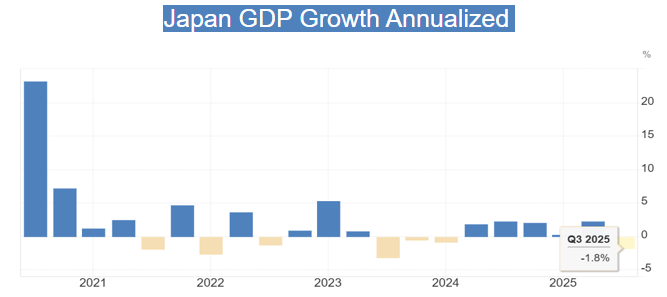

Japan’s economic growth has been notably subdued in recent years, with the latest figures showing GDP contracting by 1.8% on an annualised basis between Q3 2024 and Q3 2025. Like most advanced economies, Japan has not been immune to the inflationary pressures that followed the COVID-19 pandemic and the geopolitical shocks triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Although headline inflation of around 3% in the year to October 2025 appears modest by international standards, it represents a significant departure from Japan’s long-standing norm where average annual inflation in the 21st century has hovered around just 0.43%. This shift underscores the mounting pressure on Japanese households and highlights the government’s decision to try and shield consumers from a rising cost of living while also trying to revive economic momentum.

Although the Yen had come under pressure in the month leading up to the announcement, falling roughly 3.5%, the market’s reaction to the approval of the package itself was relatively muted. In the week following the announcement, JPY/USD remained fairly stable and the broader Yen index saw little movement. In fact, both the USD/JPY rate and the Yen index have risen by around 1% from the announcement date to the time of writing (02/12/25), suggesting investors are not viewing the package as fundamentally destabilising.

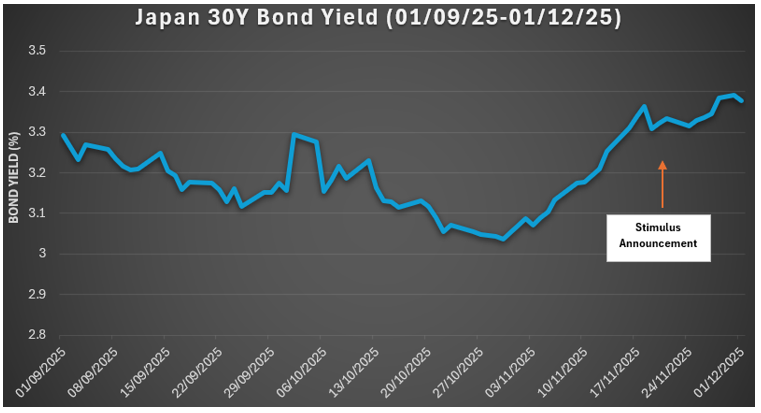

Bond yields have however been on the rise. The graphic below clearly shows how the 30Y yield had been climbing in the month prior to the package. There had been a lot of activity at the long end of the Japanese yield curve and in currency markets leading up to the announcement, suggesting that market participants had been expecting a package of similar scale. After all, Takaichi made it clear after her appointment in October that fiscal expansion was coming.

Although 30Y yields rose by around 1.65% in the week following the announcement, markets had already adjusted their expectations, resulting in a far more muted shock. By contrast, the UK mini budget caught markets completely off guard, which is almost never helpful in fiscal policy, as Truss abruptly discovered.

Japan entered this period with a fundamentally different inflation backdrop. Although inflation has risen in the post-pandemic period, it remains far more contained than the levels the UK faced in 2022. As a result, markets have been less sensitive to fears of an inflation spiral triggered by fiscal expansion.

Another reason markets reacted less drastically to Takaichi’s plan is its clearer funding structure. Around $75 billion in new bond issuance will support the package, alongside $18 billion in tax-revenue surpluses, $17 billion in unused funds from the previous fiscal year, and $639 million in non-tax revenue. Although adding more debt to an already heavily indebted economy is far from ideal, markets value transparency. This stands in sharp contrast to the unfunded nature of the Truss-Kwarteng budget, where the absence of any credible funding plan immediately raised questions about fiscal sustainability.

Japan’s approach also aligns more closely with its established monetary policy framework. The BoJ has operated under ultra-loose policy for years, and the coexistence of a weak currency and high public debt is familiar territory for investors. By contrast, the UK mini budget arrived just as the BofE was aggressively tightening policy, creating a direct and destabilising policy contradiction.

Finally, Japan remains far more export-oriented than the UK. Although its trade surplus has narrowed or even flipped in recent years, the scale of its export sector means Yen depreciation can still be beneficial by improving international competitiveness. While a weaker currency raises import costs, the cash handouts within the stimulus package help shield households from some of the pressure. For markets, Yen weakness appears far less of a systemic risk than the sharp Sterling fall seen in late 2022.

Despite both fiscal packages aiming to reboot domestic growth, markets received them in completely different ways. Japan entered this period with lower inflation, a stable and familiar monetary policy framework, and markets that had already anticipated additional fiscal support. Crucially, Takaichi outlined a clear financing plan, removing speculation over how the package would be funded and avoiding the sense of fiscal irresponsibility that defined the Truss-Kwarteng announcement.

These contrasting reactions highlight how credibility, communication, and macroeconomic context shape the success of fiscal policy. Japan’s experience shows that stimulus can be deployed without destabilising markets when it is funded transparently, communicated effectively, and aligned with broader economic objectives.

For now, Takaichi can breathe easily, but markets are rarely forgiving for long. Even well-received packages can face turbulence if execution falters or economic conditions shift.