• Crash type matters: Government intervention is only effective when aligned with the nature of the equity crash, with speculative or localised bubbles requiring far less action.

• Iceland shows an alternative: By protecting domestic stability while purging overleveraged banks, Iceland highlights how removing the problem before regulating can support long-term recovery.

• China prioritised stability: Rapid government buy-ups in 2015 reduced short-term risk and restored confidence, showing that immediate intervention can protect investor welfare even if it weakens market efficiency.

In economics, we’re introduced to the Keynesian view that an economy can settle in equilibrium even when output sits below full capacity. In a recession, this creates a clear case for expansionary fiscal policy to boost aggregate demand and support recovery. Apply that logic to equity markets, though, and things become less straightforward. Equity crashes triggered by global downturns do reflect weaker consumption, falling investment, and collapsing business confidence. But market sell-offs can also be driven by speculation, sudden policy shifts, or tax changes that have little to do with the real economy. This raises the question: in which scenarios is government intervention in equity markets justified, and how does a large coordinated buy-up of banks or direct equity holdings influence macroeconomic stability and investor welfare?

This report examines three major case studies from the 21st century: the Dot-Com Crash of 2001, Iceland’s response to the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and China’s stock market crash in 2015. Together, they show how different types of equity crashes can shape the need for government intervention and the consequences that follow.

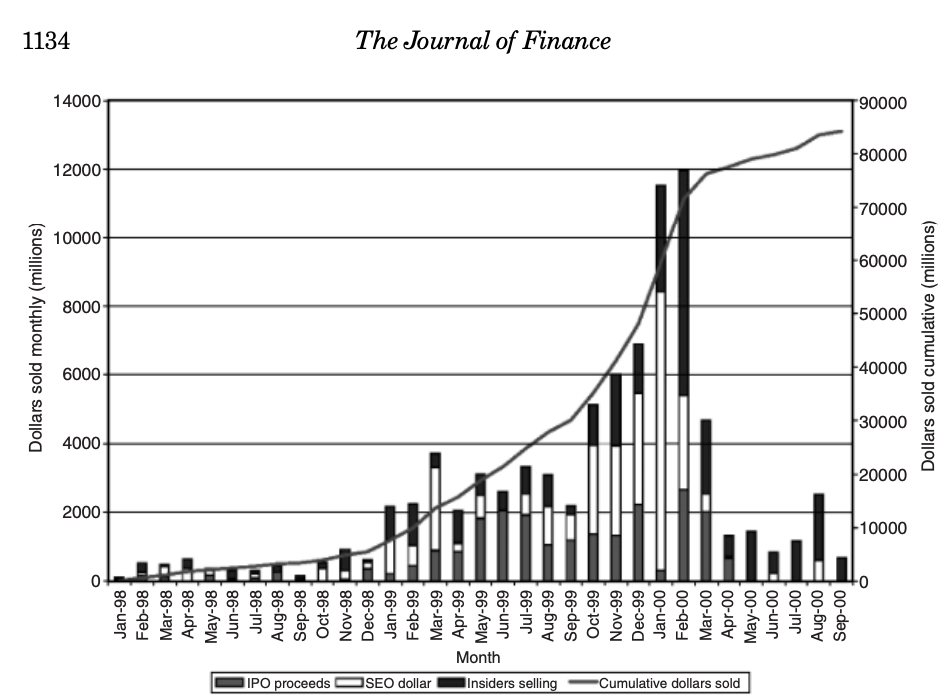

The first and simplest case study is the Dot-Com Bubble of 2001. This crash was rooted almost entirely in speculation, with corporate behaviour during the late 1990s becoming increasingly manic. A surge in equity issuance and a relentless stream of IPOs defined the period, as shown below, creating an environment where prices drifted far from any underlying fundamentals.

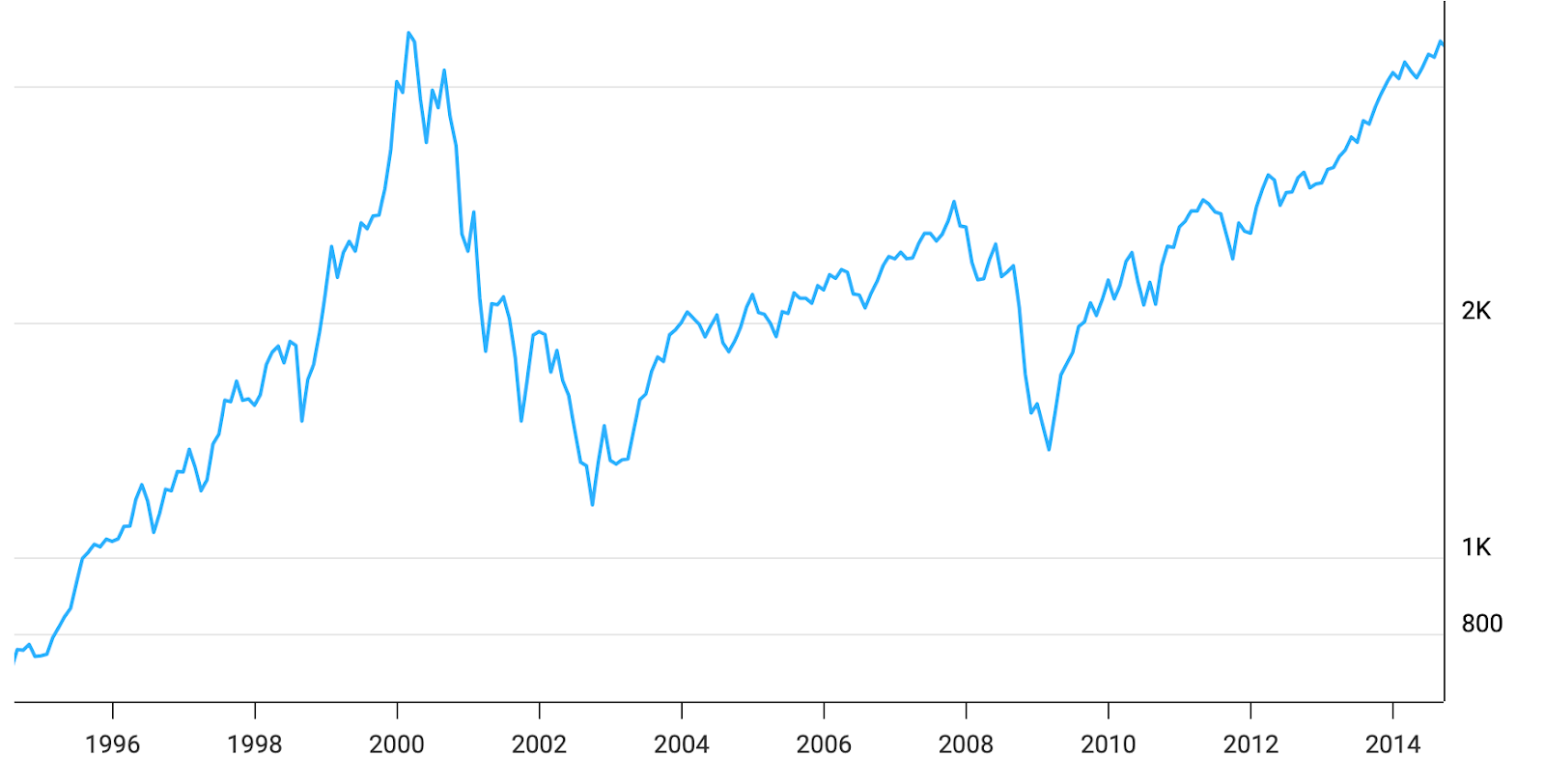

Once this bubble inevitably crashed, the NASDAQ fell by almost 80%. However governments, besides pursuing inflationary monetary policy, did little to revive fallen equity markets - which took around 15 years to fully recover.

The lack of government intervention was justified. There was no need to bail out an industry that had clearly become overleveraged. While policymakers focused on broader macroeconomic stability through fiscal and monetary tools, stepping in to protect investor welfare would have been excessive for a crash that was relatively contained. Leaving the market to correct allowed prices to gradually return to their fundamental value.

However, the picture changes when a crash reflects systemic market risk and spills directly into the wider economy. In those cases, far more aggressive intervention both fiscally and through equity markets becomes necessary.

That was certainly true in the UK. To prevent a total collapse of the financial system, the government took majority stakes in several major banks, including an 84% stake in the Royal Bank of Scotland, a 43% stake in Lloyds Bank and the full nationalisation of Northern Rock.

Iceland, however, faced an even more severe shock. Its banking sector had grown disproportionately large relative to the size of the economy, driven by heavy foreign lending. When the crash hit, more than 80% of Iceland’s financial system collapsed, wiping out roughly 95% of its stock market, nearly three times the fall seen in the S&P 500. Yet, unlike the UK, the government chose not to bail out the banks.

Instead, “The government cleaned house in all the three banks, establishing new boards and management,” explained Johnsen, Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Iceland. With $4.6bn in support from the IMF and neighbouring countries, Iceland protected domestic industries and prevented a deeper currency crisis. New banks such as Landsbankinn were created to restructure assets and provide debt relief to both corporates and households. By placing consumer deposits and essential banking services at the centre of its response, Iceland was able to purge its financial sector of “bad banks” (Matsangou, n.d.).

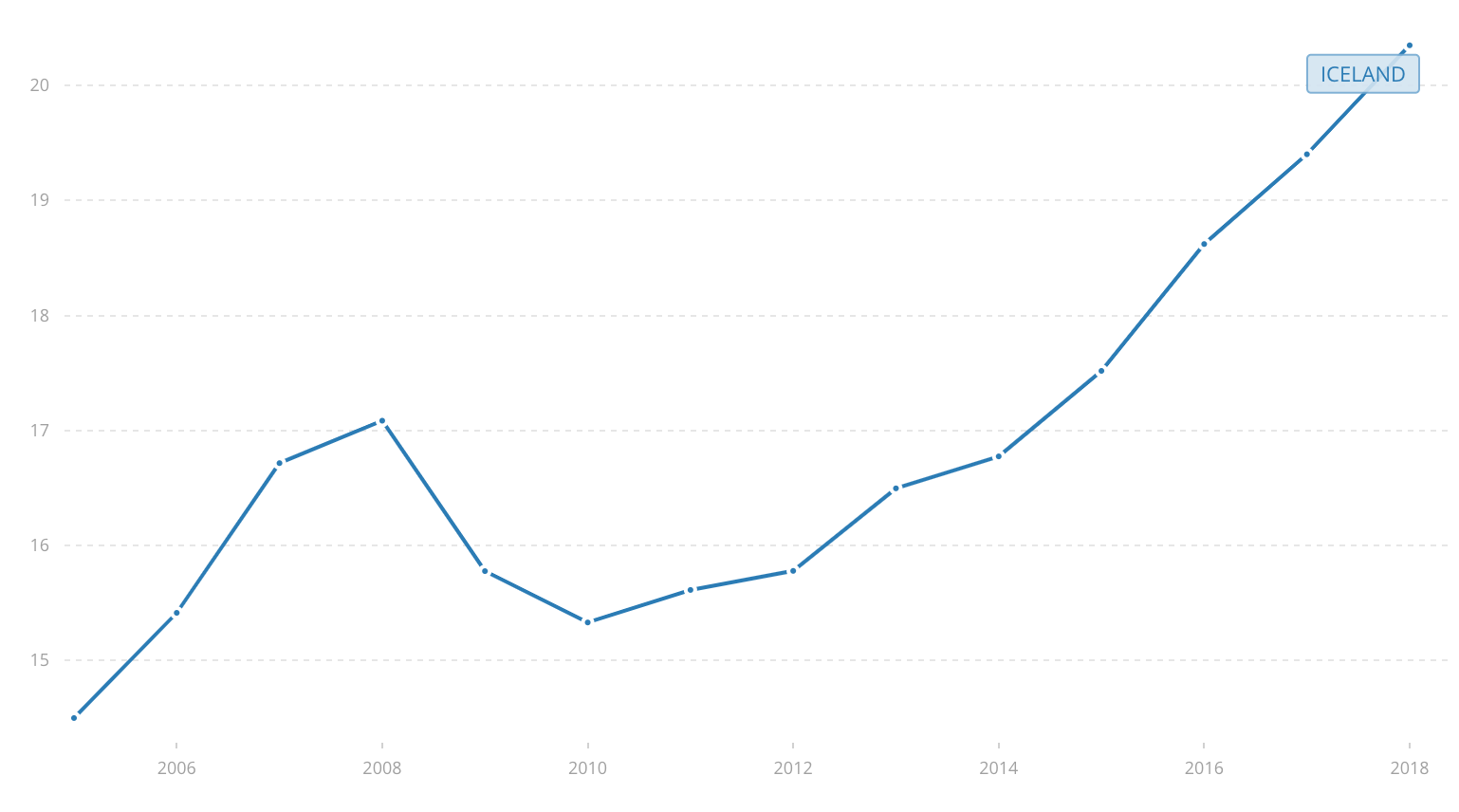

Based on this collapse, the question is how Iceland revived its economy to steady growth levels from 2010 while the UK is still trying to solve the productivity puzzle dating back to 2008. Although its rapid rebound is often linked to a more liberal approach to financial crashes, the connection is weak. In reality, Iceland’s recovery was highly specific to its own circumstances.

Much of the recovery came from structural advantages. Industrial growth was driven by its geothermal resources and expanding tourism sector. Aluminium production, which relies on large amounts of energy, operates efficiently in Iceland because energy costs are naturally low, and the industry accounts for about 16% of exports. Other energy intensive sectors, including crypto mining, contribute jobs and output. Tourism, however, is the true heavyweight. It represents about 42% of exports and made up roughly 12% of GDP in 2017, making Iceland one of the most tourism dependent economies in the world.

Iceland is therefore unlike most economies, and using its recovery as a case study for the benefits of limited equity-market intervention overlooks that uniqueness. Even if its rapid rebound cannot easily be replicated elsewhere, the way its government handled the financial system still offers meaningful lessons.

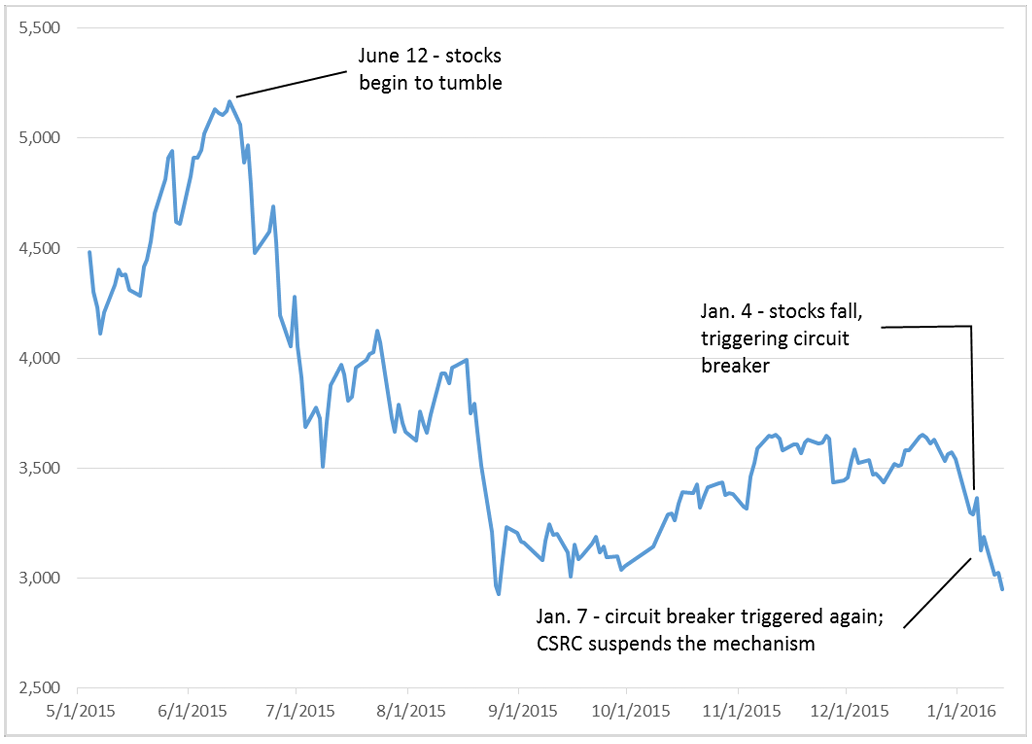

The last case study examines what happens when governments take a heavy-handed approach to equity markets. Formal leverage trading was introduced in China in 2010 through regulated brokerage houses and nonregulated online lending platforms. The latter, together with non-bank lenders such as trust companies, formed the core of the shadow banking sector. Alongside other contributing factors, this environment helped inflate a bubble that eventually burst in June 2015. New regulation restricted margin lending to fintech companies, reducing the amount retail investors could borrow to trade. The Shanghai Stock Exchange had reached a historic peak in June 2015 before falling by about 30% by July 2015 (Maiello, 2019).

China did not sit idly by watching its stock market collapse with rumours of the next financial crisis emerging. China created a “national team” consisting of the China Securities Regulatory Commission and state-owned brokerages, which resumed share purchases. The People’s Bank of China channelled RMB 130 billion (around $20 billion) into the financial system to support the currency and calm investors. For the next three months, the regulator imposed a ban on large shareholders from selling more than 1% of their stake. It also introduced circuit breakers, which halted trading if prices fell too sharply. These were later suspended because they triggered more panic, as investors rushed to sell before trading stopped.

China made no attempt to allow market forces to re-allocate resources after the crash. Even so, there were clear advantages to the speed and scale of its intervention. By the end of 2015, the Chinese stock market had recovered and even surpassed the S&P 500 for that year, gaining 12.6% across the period. Although stock markets fell again from 4–7 January 2016, the strength of the rebound showed how effective fast, co-ordinated intervention could be.

These buy-ups affected how stock markets processed information. A study by Sijia Lou examined the impact of these actions on stock synchronicity, which measures how much of a company’s returns are driven by general market movements rather than firm-specific information. The study found that intervention increased stock synchronicity. High synchronicity makes prices more responsive to market-wide changes and less sensitive to individual company data, reducing market efficiency and encouraging herding behaviour. This makes it harder for investors to value firms using stock prices, which undermines the idea of efficient markets. The paper also identified a link between investment efficiency and stock informativeness, where investment efficiency is the unexpected change in equity value associated with a unit of unexpected investment. When information quality deteriorates, valuing companies becomes more difficult, which reduces the value of the market (Lou, 2016).

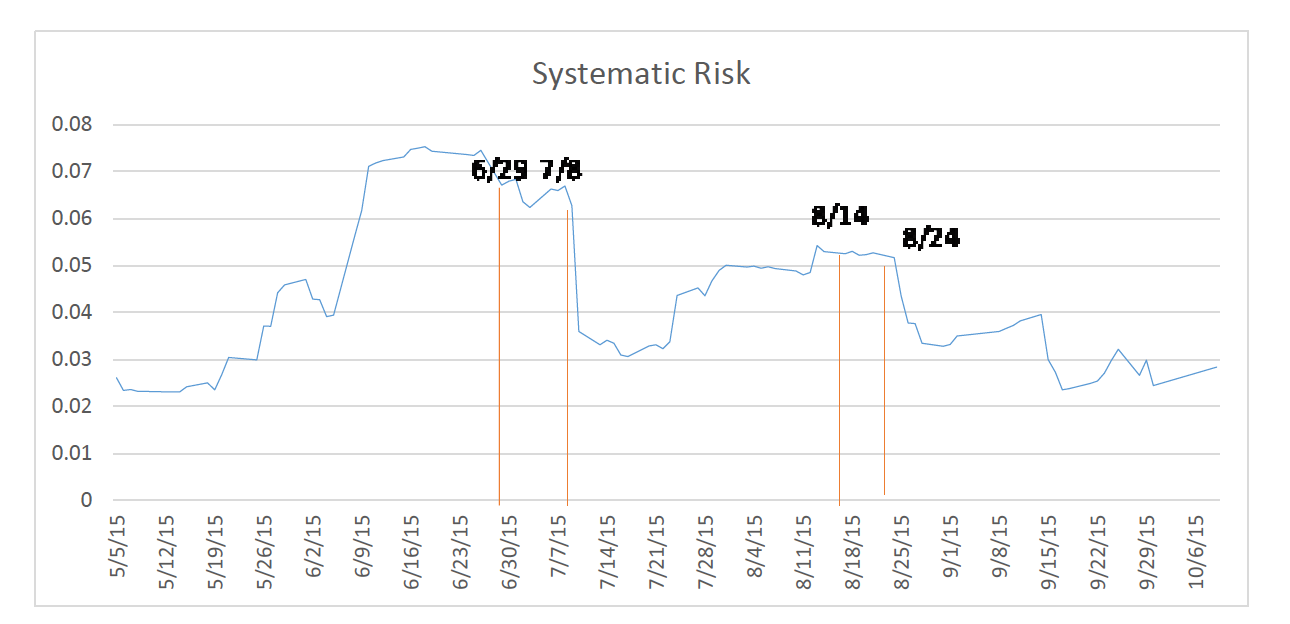

The paper did note short-term reductions in systematic and idiosyncratic risk as a result of government buy-ups, supported by the graph below. This reflects how intervention lowers the chance of a steep, sudden drop in market prices.

Overall, the research highlights a trade-off between short-term stability and the long-term efficiency of the market, and how effectively investors can value what they hold.

Fundamentally, the response of government intervention in equity markets depends on the type of crash. For more localised crashes in certain industries, government intervention is almost counterproductive when trying to uplift an overleveraged sector. For economy wide crashes, Iceland’s prioritisation of internal economic stability whilst purging the overleveraged agents in its financial system shows a different path. Instead of bailing out the problem and imposing regulation, removing the problem and then imposing regulation seems like a more sensible solution. However, if an economy’s goal is to maintain investor welfare and reduce risk as quickly as possible, a rapid government buy-up scheme is the most effective, as seen in China in 2015. Governments can learn from Iceland’s recovery strategy as a blueprint for purifying a financial system, though this must be taken with caution, as countries should not expect to recover as fast as Iceland did; it is rare to see a country with tourist volume twice the size of its population.