• Securitisation as core infrastructure: Structured credit markets transform everyday loans into investable securities, giving banks capital relief and investors diversified, customisable risk exposure.

• SPVs, tranching, and structure drive resilience: From MBS and ABS to CLOs, securitised products use bankruptcy-remote SPVs and tranche systems to manage cash flows, protect senior investors, and offer attractive yields with strong credit performance.

• Investor appeal in uncertain markets: In a world of rate volatility and tight corporate spreads, securitised products provide controlled credit risk, flexible duration, and durable income, keeping them central to institutional portfolios.

Securitised products have become one of the most important yet commonly misunderstood areas of global fixed income markets. While traditional corporate and government bonds still dominate public discussion, a significant portion of institutional capital flows into structured credit markets built on the repackaging of real economic activity such as mortgages, auto loans, and commercial property. According to a Financial Times report, demand for structured credit has grown rapidly across pension funds, insurers, and alternative asset managers as they search for yield and diversification in an uncertain environment.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the securitised products markets, covering mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, commercial mortgage-backed securities, and collateralised loan obligations. Going beyond definitions to explain not only what these instruments are, but why they exist, how they are created, and what makes them so attractive to investors of all types.

Securitisation is a process in which a pool of underlying loans or receivables, such as credit card repayments, are transformed into tradable fixed income instruments. Instead of holding individual credit exposures, such as thousands of residential mortgages, investors can purchase securities backed by these assets, typically classified through different tranches of seniority and risk.

Securitisation serves three core functions within financial markets: capital relief for originators, diversified exposure for investors, and customisable risk/return profiles.

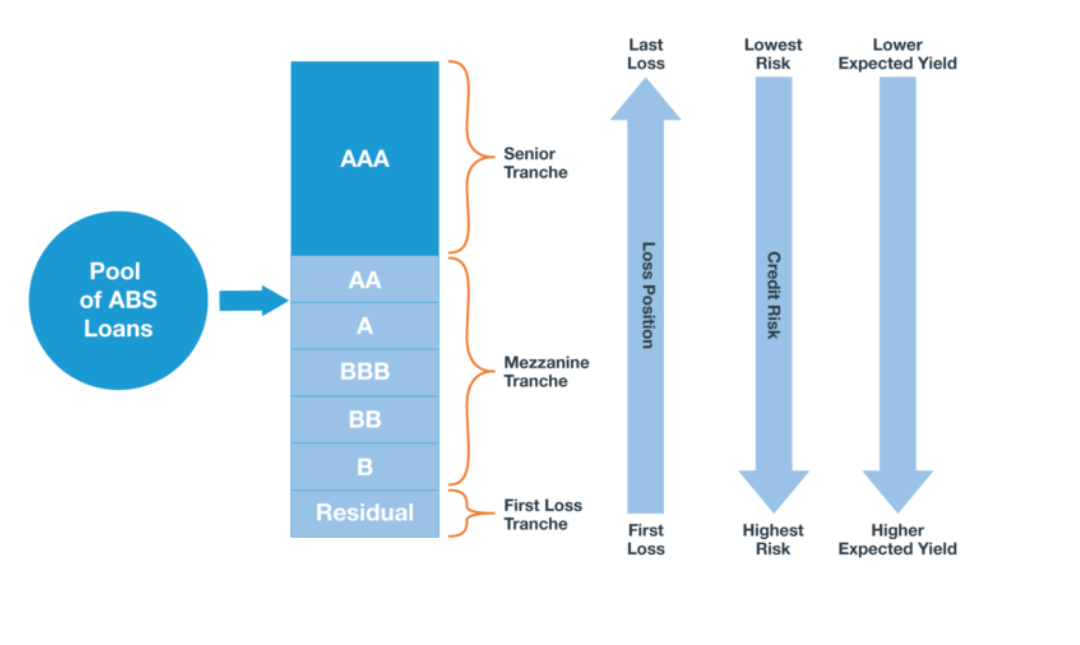

Banks convert loans into marketable securities, allowing them to free up regulatory capital whilst reducing the risk held by originators of these loans. A single security may represent thousands of underlying loans, reducing idiosyncratic risk. Idiosyncratic risk is a risk due to a unique circumstance or assets, therefore only affecting a small sub-section of the market, which can be mitigated through diversification of portfolios. Tranching allows the same underlying pool to meet the needs of different investors, ranging from AAA-rated notes to lower-rated high-yield mezzanine exposures.

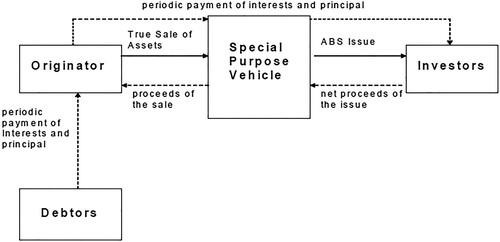

Every securitisation requires a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) – an entity that’s created to purchase a pool of financial assets and issue securities backed by their cash flows; these are structured in such a way that its assets and liabilities are shielded from the bankruptcy of its creator (the Originator). By isolating these assets from the balance sheet of the originator, the SPV provides investors with protection, while allowing lenders to recycle capital by freeing up their balance sheet. SPVs play a key role in modern structured finance, enabling trillions of dollars in funding across consumer, corporate, and real-estate markets.

Securitisation payments work through a waterfall process in two ways. Every month, homeowners pay their principal and premium payments, which go to the SPV. These premiums are paid in order from highest to lowest rated tranches, in seniority order, continuing until there is no money left/all bonds have been paid. However, if there isn’t enough money to pay all investors then losses follow the opposite in reverse seniority order and move from bottom to top. This is what creates risk and thus differentiates the varying tranches within the SPV on the same deal.

For example, if an SPV owns £100mn of mortgages, investors own bonds issued against the £100mn. However, if £5mn of bonds default, the SPV only has £95mn to repay investors with. Consequently, the principal balance of the lowest tranche is reduced to cover this loss. This means investors in the bottom tranche permanently lose £5mn as the SPV will never have the money to repay them.

Mortgage-backed securities are what they say on the tin, backed by a pool of mortgages. There are 2 main types: RMBS, Retail Mortgage-Backed Securities and CMBS, Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities and are backed by either Retail or Commercial Mortgages, with both of these categories being further divided into Agency vs Non-Agency MBS.

Agency bonds, issued through Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac, Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), benefit from either explicit or implicit government guarantees, meaning the risk of default is extremely low, making them among the highest-quality assets in global fixed income. This is due to extremely low credit risk, high liquidity and strong demand from institutions such as banks, insurers and central banks. This wasn’t always the case however, as during the financial crisis some of these were in real trouble and needed government intervention. This is because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were always thought of as being too-big-to-fail and their collapse would have destroyed the US housing market. Consequently, their support was implicitly implied, with it only being necessitated curing the 2007-08 crisis.

Non-agency MBS do not meet agency criteria and therefore carry no such guarantee instead relying on loan quality, underwriting standards, and the structural protections embedded within the SPV, which will be covered later. Post-2008 reforms have significantly strengthened these deals, with transactions featuring higher credit levels, tighter documentation, and more conservative loan pools. This is due to securitisation being a key driver of the 2007-08 crisis, specifically MBS and Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs), which won’t be covered in this article.

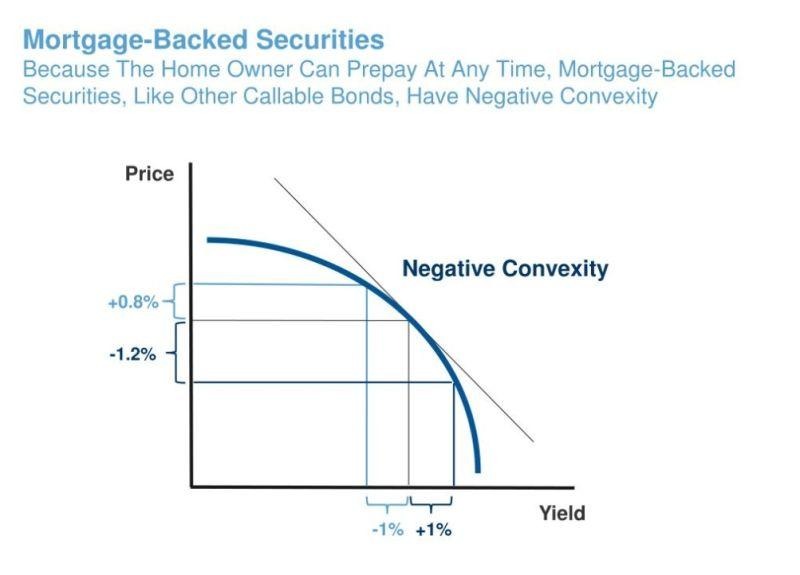

What makes MBS unique compared to other securitised products is prepayment behaviour. When interest rates fall, homeowners refinance their mortgages, returning principal to investors faster than expected. However, when rates rise, borrowers stay locked in, slowing principal repayment. This option means that MBS performance is directly linked to interest rate movements. Therefore, Agency MBS often trade at spreads that not only reflect credit quality but also the cost of hedging the negative convexity (convexity is a measure of how a bond’s yields and price vary with time to expiry, with negative convexity meaning that prices fall more when yields rise and rise less when yields fall) caused by the issue of prepayment.

This impacts MBS through prepayment as the homeowner exercises the call option on their loan by re-financing to a cheaper rate. Consequently, the MBS investor is forced out of a higher-yielding asset, into a lower-yielding asset reducing their cash flow and expected return. For this reason, asset managers and banks often rely on interest-rate swaps or Treasury futures to manage this as prepayment speeds change.

Today’s environment of high mortgage rates has slowed refinancing to lows not seen in decades whilst extending the life of existing pools and reducing cash-flow uncertainty, increasing attention for these products from investors. With spreads still attractive relative to corporate bonds, MBS are finding new demand from banks, insurers, and real-money accounts looking for high-quality yield in an uncertain period.

ABS expanded securitisation beyond mortgages and into consumer and corporate credit. Assets used for ABS include: auto loans, credit cards, student loans, and whole business securitisations (e.g., restaurant franchises). Effectively, ABS allow any cash flow generating assets to be securitised and invested in.

ABS are generally shorter in duration than MBS and are favoured due to their predictable cash flows. Non-agency MBS are often structured in a nearly identical way to ABS due to the lack of a government guarantee, with a typical AAA-rated ABS providing attractive spreads relative to equivalently rated corporates, due to structural protections such as over-collateralisation, reserve accounts, and excess spread. These are various methods used to limit losses to investors by ensuring that the SPV absorbs as much as possible before it ever reaches investors.

Excess spread is often the first line of defence as this is used to build up the reserve accounts, which cover losses first, before resorting to over-collateralisation, through the ongoing profit margin of the SPV. For example, if the SPV receives 6% interest from borrowers but only pays 4% to bond holders, then the SPV has 2% excess spread, which can be used to build up reserve accounts. Alternatively, reserve accounts can be funded through the closing of the deal as excess cash left in the SPV.

Over-collateralisation is when an SPV will hold more assets than bonds, this works as if an SPV holds £105m of mortgages; they will only issue £100m of bonds, leaving £5m as excess collateral. Therefore, if £3m of loans default then there is a cushion within the SPV, so all investors receive their premiums, however the value of the asset pool now decreases to £102m.

According to research from J.P. Morgan, ABS provide: shorter-weighted average lives (cash is returned to investors more quickly leading to shorter term lending periods), lower correlation to traditional credit (this adds diversification to portfolios as performance depends on consumer payment rather than corporate earning cycles), high recovery rates across senior tranches (senior tranches rarely, if ever, miss any principal payments).

These features make ABS popular with money market funds, insurers, and bank treasury desks. Institutions buy ABS because they provide strong historical performance during downturns, short weighted-average lives, low correlation to conventional credit, and high recovery rates on senior tranches. Money-market funds, insurers, and bank treasury desks have all leaned heavily into this market, finding that the structural safeguards of the SPV often make ABS exposures more resilient than traditional corporate debt due to their low risk profile, making them a safe place to park cash.

The most structurally dynamic area of securitisation is the Collateralised Loan Obligation (CLO) market. CLOs are SPVs backed by pools of floating-rate leveraged loans - debt issued by sub-investment-grade companies. Unlike static ABS or CMBS pools, CLOs are actively managed, with managers buying and selling loans within defined limits to optimise portfolio performance. Senior CLO tranches have delivered attractive risk-adjusted returns and benefit from floating coupons, making them particularly valuable in higher-rate environments, and investors have consistently rewarded this structure. The structural enhancements introduced since 2008 and more robust documentation, have contributed to the extraordinary statistic that AAA-rated CLO tranches have never experienced a default.

A CLO will hold 100-300 different corporate loans across many sectors and issuers. This helps to diversify risk, unlike other types of Securitised products which only hold a few corporate bonds. This means that a single default has a very small impact and is therefore unlikely to cause a knock-on effect for the rest of the CLO.

The investor base is therefore understandably diverse: insurers, banks, and pension funds dominate the AAA and A tranches, while hedge funds and credit-opportunity vehicles pursue the higher-risk equity layers. CLOs have become a critical engine of financing for leveraged buyouts and private credit, with their multi-hundred-billion-dollar footprint influencing corporate credit markets far beyond the securitisation sector itself. With yields in traditional credit tightening, CLOs remain attractive because they offer floating-rate exposure, strong diversification, and high structural resilience. This is beneficial as it protects investors from duration risk, therefore making floating rate assets preferred during periods of moving yields

Securitised products remain one of the most important markets in modern credit, freeing up capital for housing, consumer finance, and commercial real estate at a scale that traditional lending simply cannot match. They also supply much of the high-quality collateral required to keep markets functioning, making them essential for day-to-day financial stability.

In my opinion, what makes them especially relevant today is their ability to offer investors control over both credit risk and duration exposure at a time when rate volatility and macro uncertainty remain elevated. Especially with spreads in many parts of corporate credit becoming tighter, particularly in ABS and high-quality CLO tranches, due to strong demand, refinancing activity, and technical flows. Securitised products continue to provide attractive yields alongside structural protection that has been strengthened significantly since 2008. For these reasons, I am confident that they will continue to remain a central market for institutional capital, particularly as investors become increasingly selective in management of risk during this uncertain period and talk of an AI bubble.

Securitised products play a key role in global capital markets, linking economic activity on a personal level with institutional capital in a way that is scalable and resilient. Through mortgage pools, consumer finance receivables, commercial real estate loans, or leveraged-loan CLO structures, these instruments allow risk to be redistributed across investors with different appetites and time periods. Their complexity often over-complicates the simplicity of the underlying idea: transforming thousands of individual loans into investable securities that deliver predictable cash flows and diversified exposure.

Understanding how securitisation works, from SPVs, the waterfall payment system to the protections offered through tranching, is fascinating and highly important for anyone looking to diversify their portfolio. As investors navigate an environment of falling inflation, tighter financial conditions, and heightened sensitivity to rates, securitised products will remain a key source of yield, stability, and structural flexibility across portfolios.