The markets are recalibrating as OPEC’s core mandate is entering a period of expansion. There have been growing concerns among the OPEC members about their market shares declining from 32–33% in 2017–18 to 27.4% of global supply as of late 2023, coupled with growing non-OPEC leverage on crude oil production. The chart below highlights the global shift in contributions of OPEC participants relative to non-OPEC towards global crude oil production:

While OPEC members were holding back on supplying over 2 million barrels per day, non-OPEC members such as Brazil and Guyana were rapidly scaling their offshore projects, and as a result, their supply growth covered the majority of the global demand increase. To mitigate these changes, OPEC made the formal decision for the gradual unwinding of cuts from April 2025 onwards, with an increase of 548,000 barrels per day starting September 2025.

The macroeconomic consequences extend beyond the asset itself, with its impact rippling through to global inflation, monetary policy, and global growth rebalancing. In practice, central banks might interpret the increased oil supply as disinflationary headline CPI, which may start to facilitate dovish trends if increases persist for long enough. For oil-importing countries, lower oil prices act as a quasi-fiscal stimulus for importers because this enables households to retain more disposable income and cuts input costs for many businesses, which promotes consumption. A $10 decline in oil prices can cut import bills by around $45–50 million per day or $16–18 billion annually. On the other hand, exporting countries lose revenue when oil prices fall. This widens the fiscal deficit, and this results in budgetary stress for countries like Saudi Arabia, which may either reduce spending, borrow more, or draw on sovereign wealth funds. This transfer of income from exporters to importers is expected to redistribute global demand, which disproportionately supports emerging economies in Asia who account for nearly half of global oil imports.

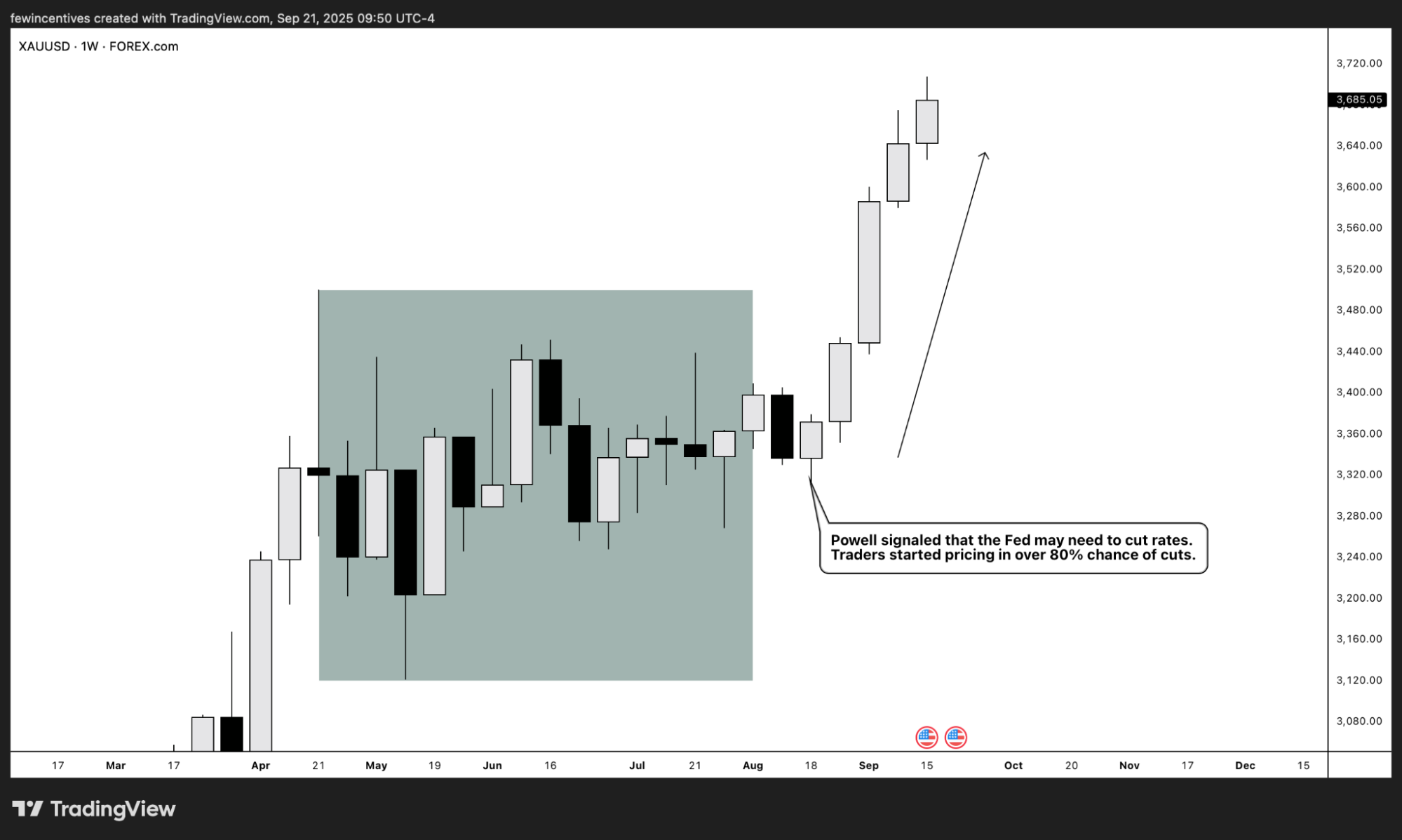

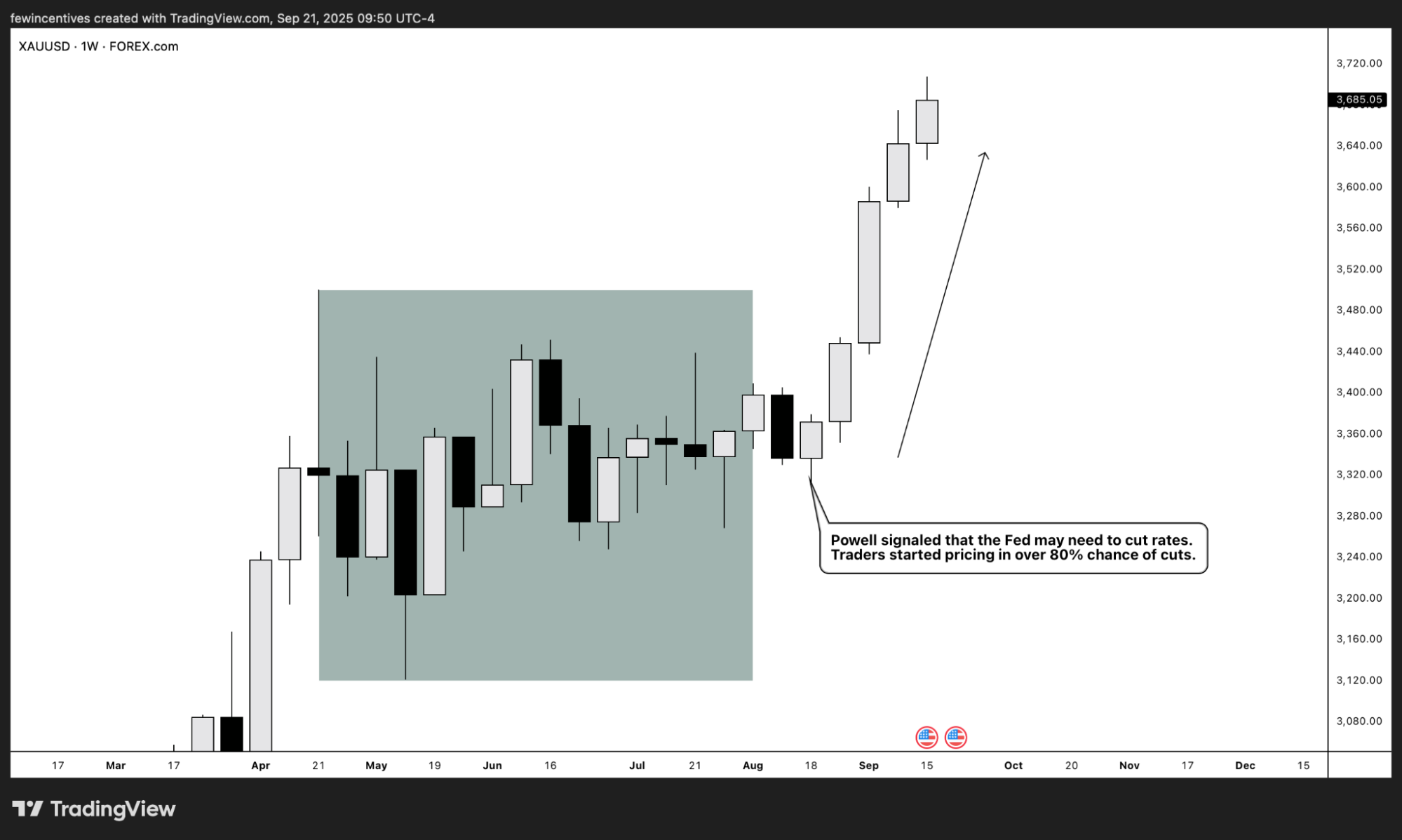

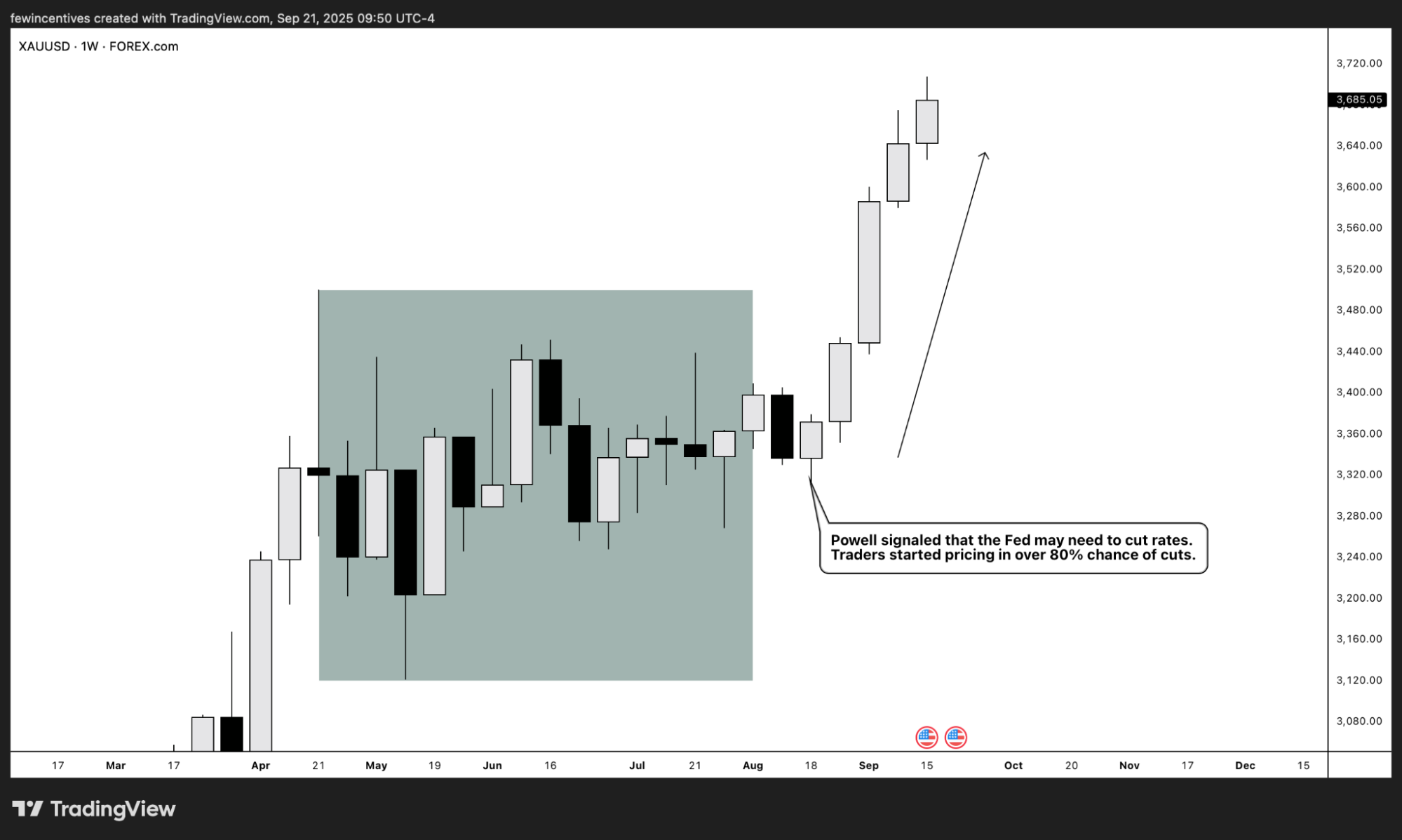

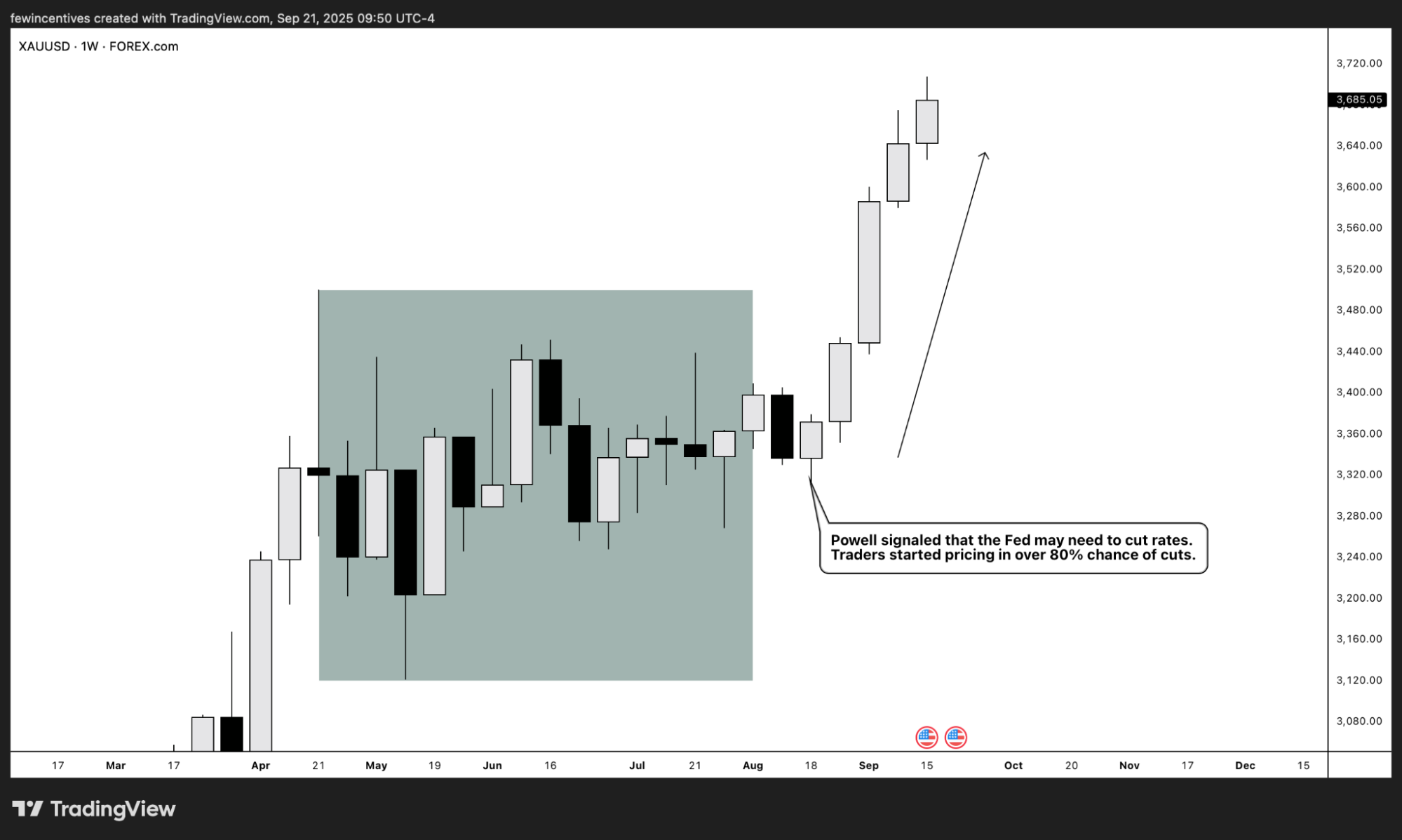

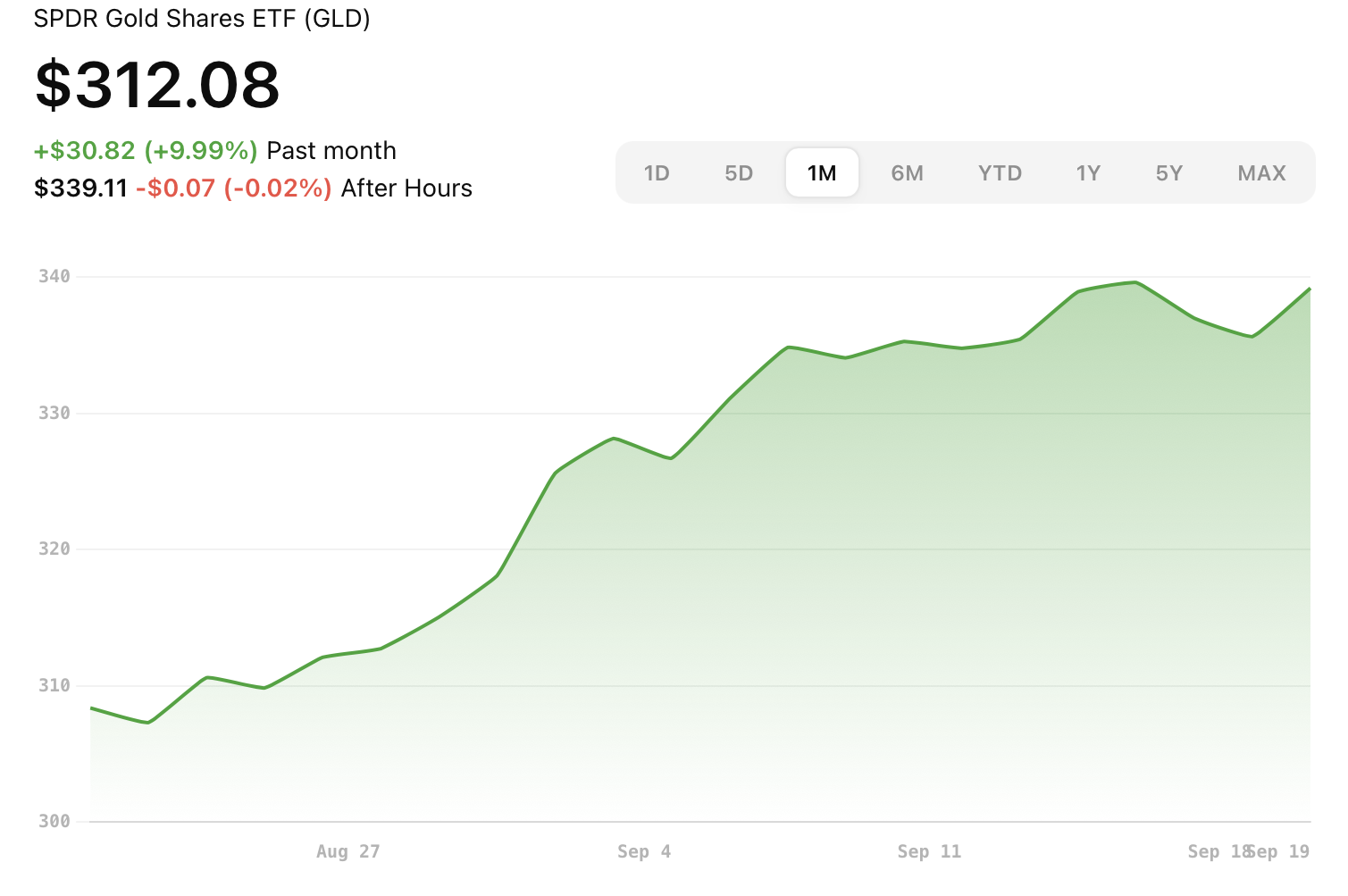

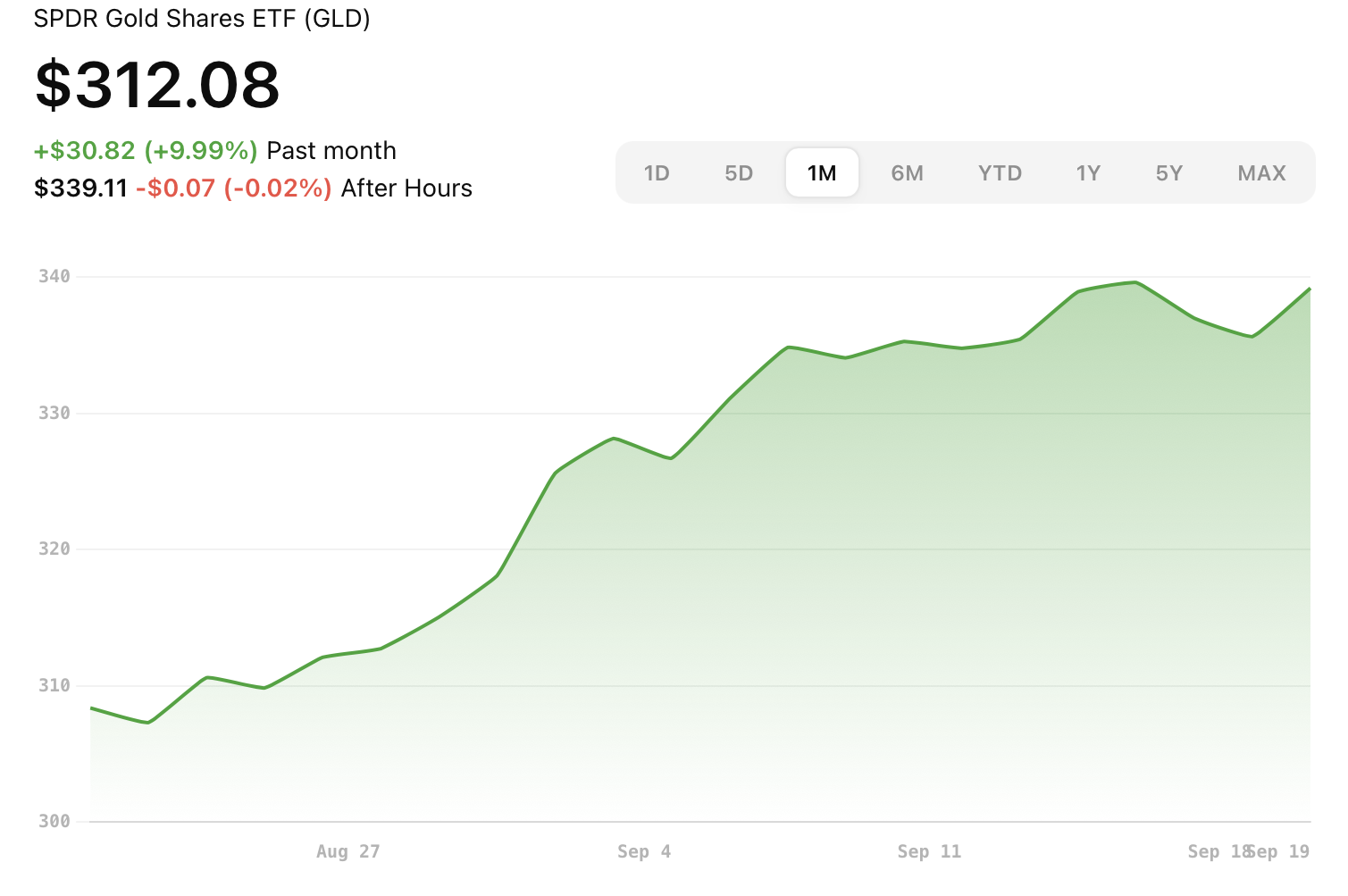

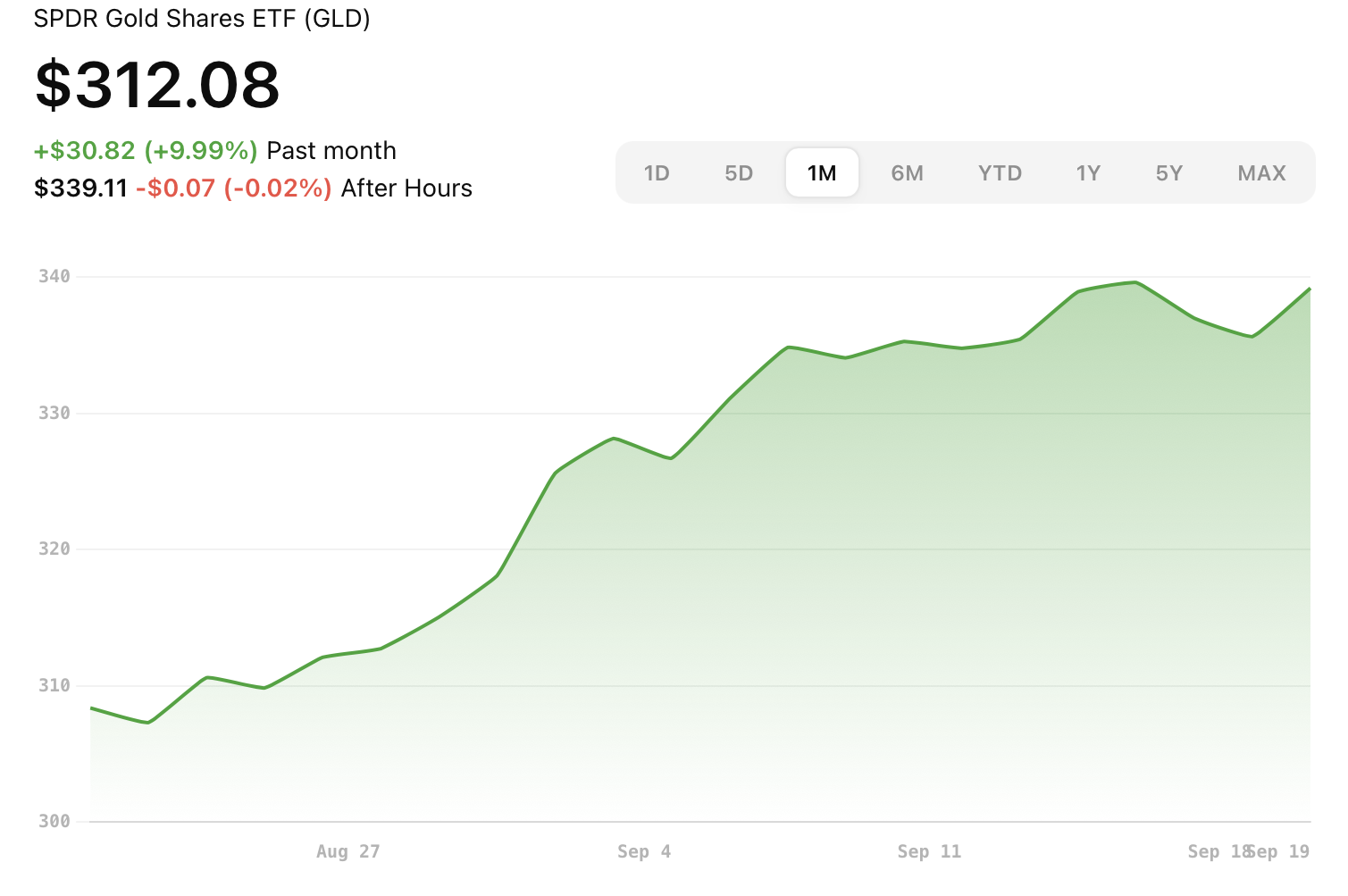

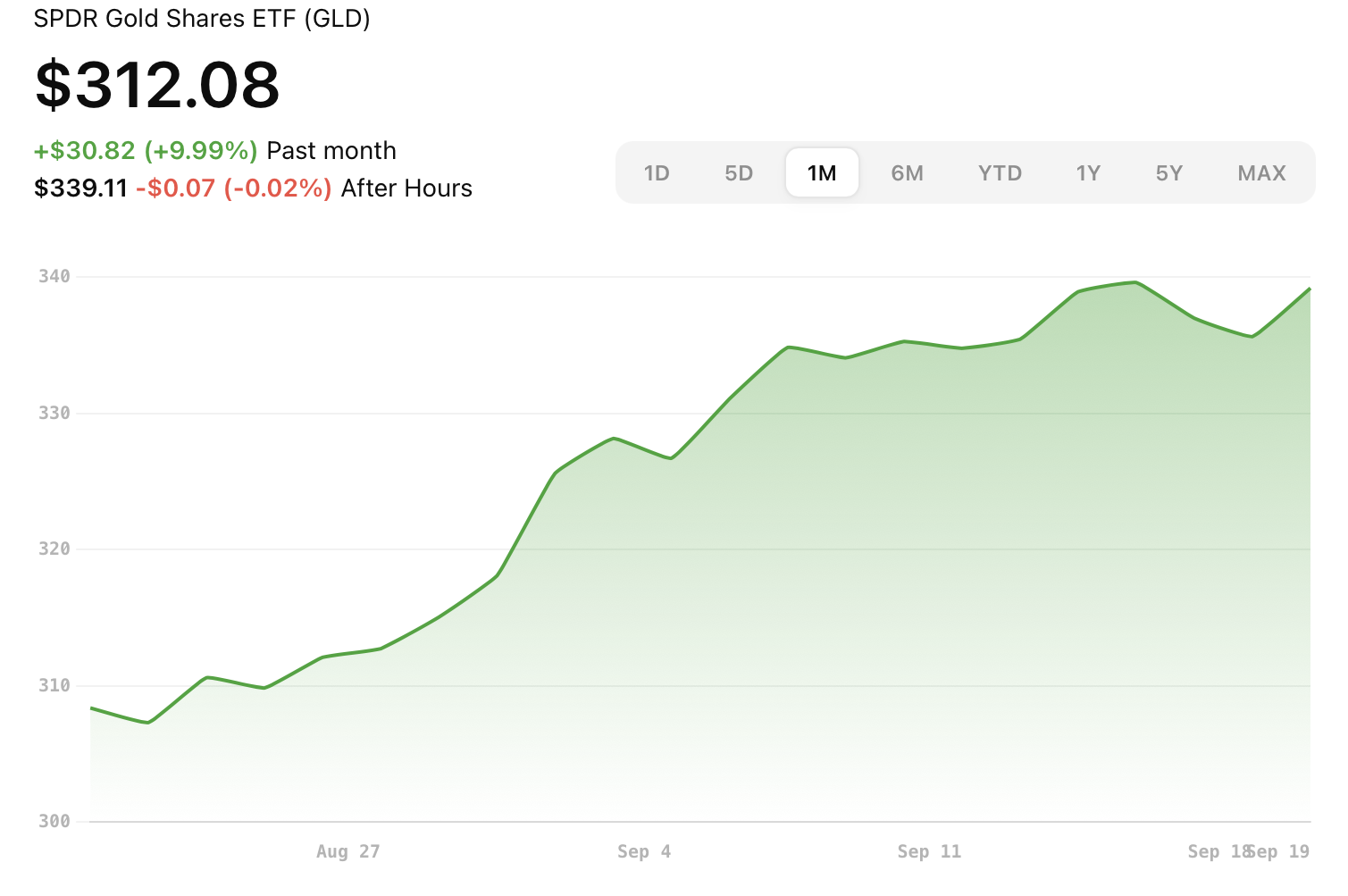

The latest adjustments highlight a structural shift in investor sentiment and opportunity cost for gold, and are driven primarily by the FED’s decision to cut interest rates to accommodate the softening of the labour market, despite elevated inflation. To understand the current adjustment, it is necessary to examine the effects of real yields, inflation, and ETF inflows on the sharp rally in the price of gold.

U.S. nominal yields declined modestly in September, while breakeven inflation remained flat at 2.35%, which resulted in real yields gradually falling towards negative territory. This suggests that the sharp rally in gold was a result of a shift in real yields rather than a rising inflation expectation. Gold’s near inverse relationship with real yields and its non-yielding property increases the attractiveness and reduces the opportunity cost of holding assets like gold.

As for ETFs, the SPDR GLD has received significant inflows with a Total Net Asset Value (NAV) of approximately $117.11 billion, representing about 31.98 million ounces or 994.56 tonnes of gold held in trust.

As of September 19th, U.S. ETF flows highlighted $1.56 billion into GLD, indicating a strong investor preference for gold-backed assets amid uncertainty with elevated inflation. These inflows, aligning with falling real yields, have supported an unstoppable rally, and the consistency of GLD inflows over the past several months indicates a genuine shift in investor sentiment.

Powell and His Cuts:

The Federal Reserve’s aim has shifted from fighting inflation to balancing growth risks with price stability. Markets now expect cuts in the coming months and have priced these in, as shown by recent rallies in U.S. equities. Lower rates will have effects throughout the bond market, reducing short-end yields and steepening the curve if long-term inflation expectations stay anchored.

Cuts are intended to support growth, but they also lower the barrier for risk-taking. Cheaper borrowing costs encourage more issuance in both corporate bonds and structured credit markets. For investors, this raises the question of how much credit risk to accept in exchange for higher yields, particularly if the economic outlook remains uncertain. This is largely due to recession worries in the coming months, which may dampen confidence and reduce animal spirits within the economy.

What The Curves Tell Us:

The yield curve remains a widely watched signal of market sentiment. Recently, an inverted curve has been a dominant feature of Treasury bond markets, where short-term yields exceed long-term ones — a sign that has historically pointed to recession risks. If Powell follows through with cuts, the curve could steepen as short-end rates fall, though long-end yields may stay capped due to slow growth expectations.

For portfolio managers, curve positioning is key to decision-making. Investors unwilling to take on much risk may prefer longer-duration Treasuries, locking in yields before further cuts. Others may prefer to stay in shorter-term bonds, depending on their risk appetite and their expectations for the Fed’s direction.

Structured Credit Under Pressure:

Credit markets will feel the impact of looser policy in different ways. On one hand, lower rates provide relief to borrowers, reducing default risk. On the other hand, if spreads widen, it reflects caution about credit quality. High-yield bonds and leveraged loans will be most affected given the variance in credit quality, while investment-grade credit should benefit more directly from cheaper refinancing.

Securitised products such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and asset-backed securities (ABS) will also be influenced by rate cuts. Falling rates can trigger prepayments in MBS, shortening duration and creating reinvestment risk for investors. ABS linked to consumer credit such as auto loans and credit cards may face rising stress if household balance sheets weaken. Even in a lower-rate environment this remains a real risk amid recession concerns for the coming year. As a result, demand for ABS may decline as banks and investors move to hedge exposures and avoid a repeat of the dynamics seen in 2008.

The outlook for global markets remains on a tightrope. OPEC’s decision to gradually increase output has the potential to ease headline inflation for oil-importing economies while placing fiscal strains on exporters and redistributing global demand. In parallel, gold’s resurgence reflects not only a technical shift in real yields but also deeper changes in investor behaviour, as risk aversion fuels sustained inflows into ETFs. Fixed income markets are recalibrating to a new phase of policy easing, with the yield curve, credit spreads and securitised products each signalling the trade-off between supporting growth and recognising underlying vulnerabilities. For portfolio managers and policymakers alike, the challenge is to navigate these crosswinds without underestimating their combined effect on economic indicators. While uncertainties remain, the broader message is clear: oil, gold and bonds are not isolated but rather interconnected drivers of global rebalancing. Recognising and understanding this relationship will be essential to managing risk and capturing opportunity.