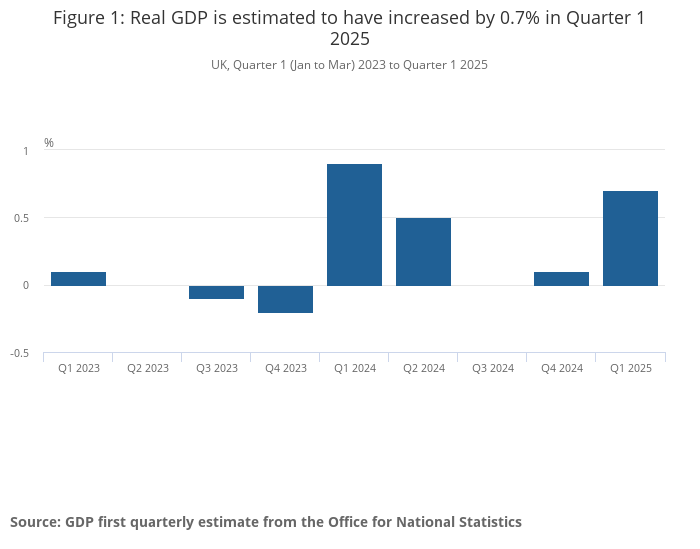

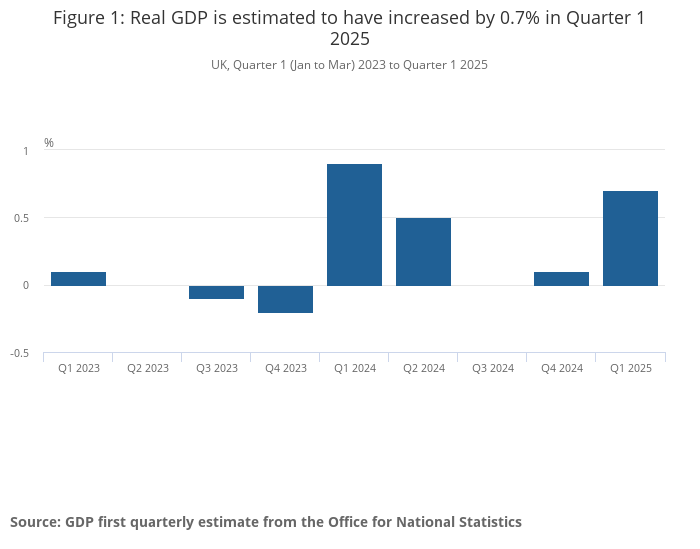

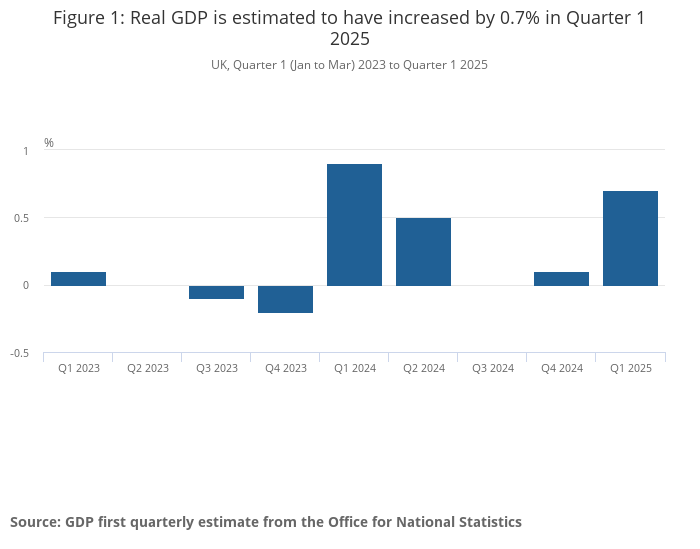

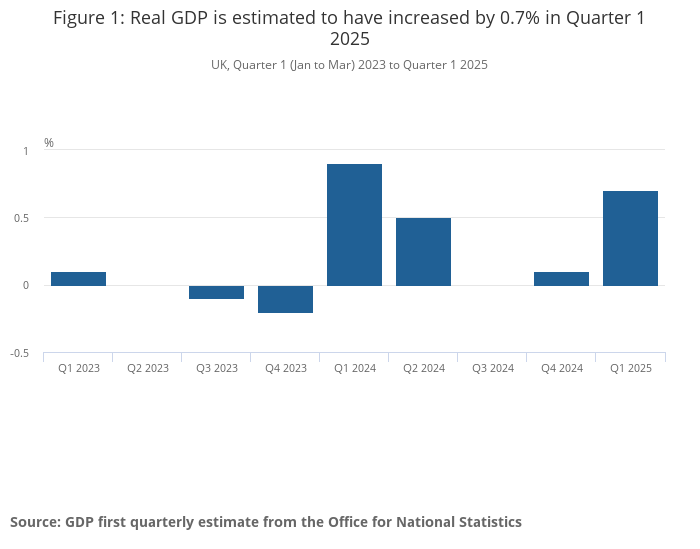

A change in ministers didn’t bring an immediate change in fortune, with limited growth over the past year. The graph from the ONS shows a strong, higher-than-expected Q1 with 0.7%, followed by a discouraging -0.3% in April and -0.1% in May (ONS, 2025).

The overall year’s growth just under 1% is a far cry from Labour’s target 2.5% per annum (Investec, 2025). What’s weighed on growth?

The two main recent factors have been tax rises and Trump’s tariffs.

Overall, apart from the boosted Q1 growth, driven by higher services and production output (ONS, 2025), (most likely sped up trade output in anticipation of tariffs), growth was rather meagre in this first year. What can we expect going forward?

In the short run, the situation looks bleak, with forecasts expecting 1.1% on average in 2025, suggesting flatlining for the second half of this year (GOV.UK, 2025). The IMF’s 1.2% puts the UK as the 3rd fastest growing advanced economy this year - encouraging but still limited growth looking ahead. There are a few factors creating this pressure:

Monetary policy - The recent spike in the inflation rate to 3.6% further confuses Andrew Bailey and the BoE’s interest rate decision next week. Cooling wage growth, weak economic growth and consumer demand might convince the Monetary Policy Committee to pursue a cut - it is hard to predict.

Fiscal policy - It is widely expected that Reeves will need to raise an extra £20bn in revenue in the Autumn Budget (FT, 2025), on the back of welfare U-turns with disability benefits and winter fuel payments - a “ticking tax timebomb” to quote Mel Stride (The Guardian, 2025). This is necessary as the UK’s debt has now hit 96% of GDP. As we brace for impact to rebuild this headroom, consumer spending and business confidence should continue to trail.

The global picture - The trade uncertainty as well as geopolitical tensions don’t seem to be reducing, further worsening the conditions for growth.

In the longer term, some of Labour’s policies should help boost growth:

Consumer investing - there will be a renewed attempt to boost UK consumers to invest (in UK shares), powered by an industry-funded national advertising campaign, potentially pouring money into UK-based companies (FT, 2025).

Financial services industry - At the annual Mansion House speech, Reeves unveiled a “Financial Services Growth and Competitiveness Strategy”, aimed at cutting back regulation in the UK financial services industry. She claimed that regulation is “a boot on the neck of businesses, choking off the enterprise and innovation that is the lifeblood of economic growth”. Reforms include reviewing ringfencing rules between retail and investment banking that were introduced post-2008 (these are similar to the so-called ‘Chinese Wall’ between the public and private parts of a bank) (FT, 2025).

This is timely to restore London’s edge as, despite being one of the UK’s biggest sectors, having the highest share of financial services exports in the G7, the sector shrank 7% from 2010-2023, compared to the UK’s GDP growth of 28% in the same period (FT, 2025).

A long term plan - There appears to be some thought put towards a strategy over a longer horizon, with the Labour government publishing an Industrial Strategy, the 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy and 10-year plan for the NHS. Their success will depend on how efficiently they are implemented and how joined up the different departments can drive towards growth.

Planning reforms - these are underway, with a few key steps being ending England’s ban on onshore wind power, a third Heathrow runway and reinstating a planned railway between Cambridge and Oxford. (The Economist, 2025) However, none of these will create an impact for nearly 10 years.

Investment and defence - Finally, the government has been keen on increasing public and private investment. The relatively new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology will get a £3.8bn increase in its yearly capital budget, outpacing inflation, and potentially leading to significant gains in a strength sector for the UK. This comes along with a smaller £1.8bn for transport, deemed to be insufficient to develop UK infrastructure. We also have £9bn towards energy and net zero and a massive £14bn going to defence, both forming over 60% of Labour’s increased investment (FT, 2025).

Defence has been one of the key differences between last summer and now: it has ballooned into a far bigger priority than expected, in a world now shaped in the image of the White House’s expectations. Whilst there are spillovers from higher arms purchases and R&D with growth, it is unlikely to be a silver bullet, highlighting the trade-offs at the heart of government spending.

To conclude, the Labour government have played their hand decently in a world that looks quite different to when they came into power a year ago, embroiled in headwinds and uncertainty. Rachel Reeves was forced to raise taxes to correctly balance the books, and they have taken a toll. The year ahead lacks promise, and the 2.5% goal seems otherworldly, but Labour will continue to look to keep UK debt sustainable whilst not slashing growth prospects - an unenviable task.