• Green bonds enter the mainstream: Green bonds have grown into a $2.7tn market, and the fading of the “greemium” shows investors now judge them on financial strength as much as ethical appeal.

• Credibility depends on clear standards: Greenwashing and fragmented global rules continue to threaten trust, making strong oversight and frameworks like the EU Taxonomy essential for ensuring that capital supports real environmental outcomes.

• The climate finance gap remains huge: Despite rapid growth, nearly $8tn in annual funding is still missing to meet global climate goals, with developing economies most constrained and “Just Transition” goals weakened by limited support for workers and communities.

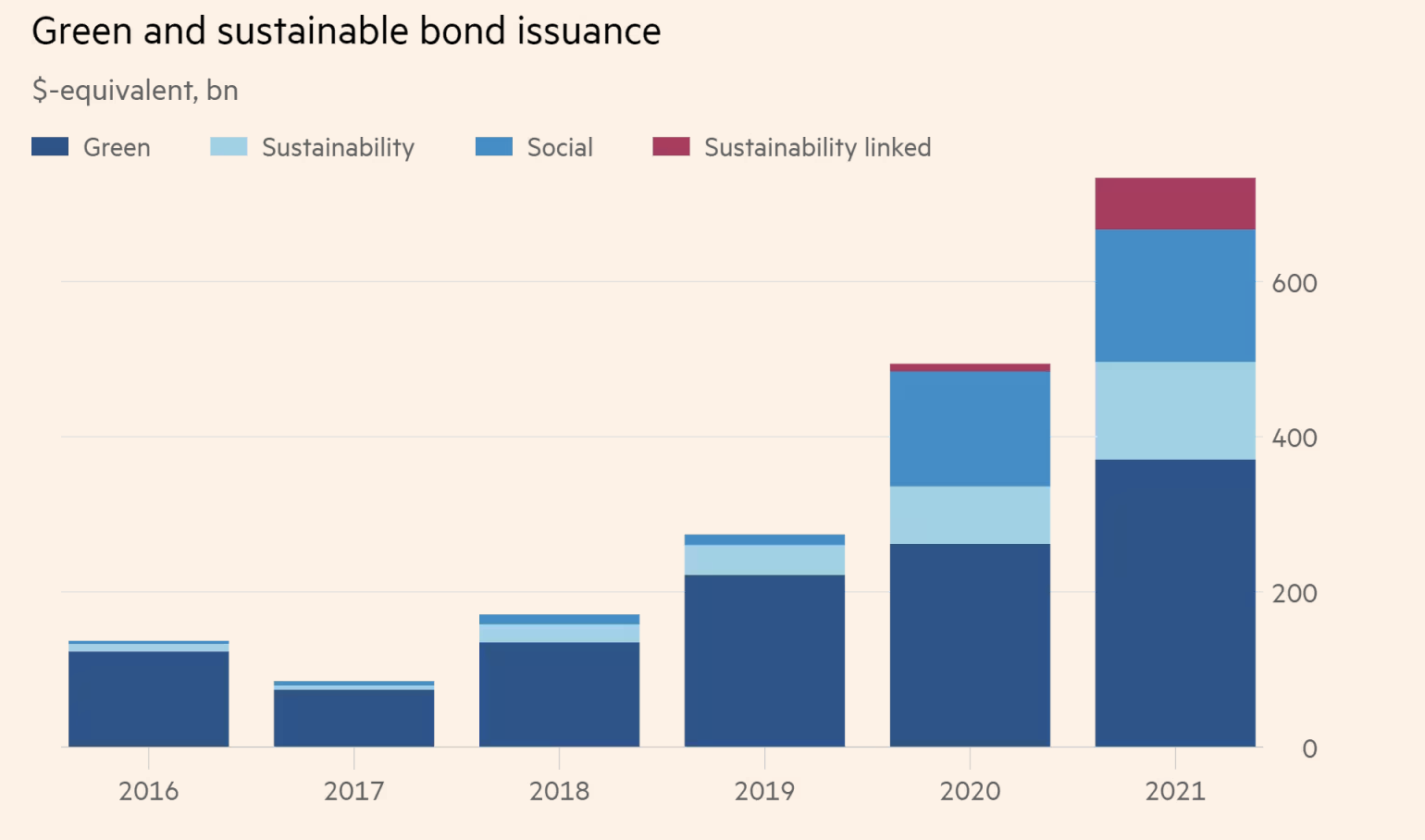

Green bonds have rapidly grown from a market capitalisation of just $500bn in 2018 to more than $2.7tn in 2024, demonstrating how an experiment in socially responsible impact investing has developed into one of the fastest growing areas of global finance. Whilst its trajectory is impressive, it is important to consider that they were designed to raise capital to meet critical funding challenges. So, are these debt instruments really driving the environmental impact they set out to deliver?

The market has matured, as corporate firms now dominate issuance of these products with a 52% share, overtaking development banks such as the World Bank, which sold the first green bonds in 2008. Encouragingly, the public sector has also played a key role in the transformation of this financing tool, as broader GSSS (Green, Social, Sustainability, and Sustainability-Linked) bonds sales have surpassed $5.7tn cumulatively, with Europe and the US driving nearly half of global issuance volumes. More promisingly, the green premium (“greemium”), which is a yield discount investors once accepted to support sustainable projects, has largely disappeared, leading spreads to be almost identical to conventional sovereign/corporate bonds. This signals that green bonds are now mainstream credit instruments competing on full financial merit, rather than a mere badge of virtue for ESG-focused investors.

The resulting capital raised from these bonds is bound by the ICMA Green Bond Principles, which mandate funding for environmental projects. In particular, renewable energy investments dominate almost a quarter of revenue allocation. Meanwhile, clean transport has emerged as a major allocation category alongside it, attracting substantial capital for green transport modernisation efforts. Despite this, credibility remains weak due to greenwashing, where firms overstate and exaggerate the environmental impact of their schemes.

This is largely down to a lack of international consensus on green project standards resulting in a fragmented regulatory environment. Whilst Europe has been stricter in its framework by having a legally binding EU Green Bond Standard, requiring at least 85% of bond proceeds to align with the EU Taxonomy (its official list of environmentally sustainable activities), other regions lack the same conviction. In other places, firms can pay between $10,000 to $50,000 to label their debt as “green”, thus making the case for much stronger oversight to prevent ‘brown bonds with green wrapper’ enduring. Alarmingly, one study even finds that many Chinese ‘green’ bond issuers were in fact simply increasing fossil-fuel energy output, which raises serious integrity concerns regarding the impact of this credit product in creating meaningful ecological impact.

I suggest that to effectively combat such greenwashing, the market must implement standardised rules that strictly and legally define what constitutes a sustainable investment, thereby preventing the mislabelling of non-compliant projects. This regulatory clarity must be reinforced by mandatory third-party verification to independently audit issuer claims, alongside rigorous post-issuance impact reporting to ensure capital is continuously delivering the promised environmental benefits rather than still supporting conventional energy production. Finally, to ensure no corners are cut when reporting project impacts, strict penalties must be set to act as a strong deterrent for foul corporate behaviour.

However, a binary ‘green vs brown’ distinction risks ignoring the huge capital needed to decarbonise heavy industries like steel, cement and aviation, which cannot switch to renewable energy soon enough, without significant financial commitment. To bridge this gap, transition bonds are emerging as a key instrument to tackle this problem, as exemplified by Japan’s sovereign ‘Green Transformation’ (GX) bonds, which aim to raise 20tn Japanese Yen to fund technologies like hydrogen steelmaking and ammonia co-firing.

The private sector is also testing this out, similar to the green bond market’s formative years, with Swedish steelmaker SSAB securing green financing for fossil-free sponge iron. This is in sharp contrast to ArcelorMittal which has faced headwinds from their Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLB), as rising energy costs and policy uncertainty in Europe has forced delays in green steel projects, resulting in SLB yield rates rising, as KPIs were missed. This divergence highlights an evolving market that is increasingly differentiating between credible, realistic transition plans and vague future promises. Consequently, there is a growing demand for issuers in high-carbon sectors to provide robust, science-based strategies that prevent ‘carbon lock-ins’ (investments in emission-intensive infrastructure that are difficult to replace), rather than relying on green finance to make small, incremental changes.

Despite the legitimacy of these funding mechanisms being debated, they are necessary given that approximately $9tn is needed to be invested every year by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement climate goals, yet current expenditure stands at just $1.2tn per annum. In particular, developing economies face a $2.4tn yearly shortfall, which is concerning as they are less likely to contribute capital to these environmental initiatives given the pursuit of greater economic growth through cheap fossil fuel, and are responsible for a large part of carbon emissions today as well. Despite green bond issuance being forecast to exceed $800bn by 2030, the funding gap remains vast.

However, innovations in digital and tokenised bonds promise to cut issuance costs through blockchain technology, making sustainable finance cheaper, faster and more transparent by cutting intermediaries and broadening access for more investors. Whilst certainly welcome, these gains remain small against the substantial funding deficit.

Moreover, even if capital is available to deploy towards sustainable projects, how this money is used is just as important a question as if financing is available. The flow of capital to the Global South reveals a troubling disconnect between the rhetoric of a ‘Just Transition’ (a framework for shifting economies away from fossil fuels and high-carbon industries in a way that is socially fair and equitable) and the true reality of budget allocation. As a case study, implementation data from South Africa’s $8.5bn Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) shows that while loans for hard infrastructure are available, grand funding for the people most affected by this transition is chronically insufficient, with less than 1% of identified grant needs allocated to skills development for workers in coal-dependent regions like Mpumalanga.

As these employees aren’t getting the retraining and support they need to transition to other industries with better working conditions and salaries, this makes the ‘Just Transition’ neither “just” nor sustainable - it’s a transition in only its name if it abandons the people it affects the most. Similarly, in the Philippines, the Asian Development Bank’s Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) is attempting to allocate private capital to retire coal plants like the SLTEC facility early to decarbonise the country’s economy; however, methods to fund the retraining of displaced workers remain complex and under-scrutinised. All in all, unless markets innovate to value social outcomes for citizens rather than just environmental progress (perhaps through transition bond schemes that ring-fence proceeds for community upskilling in high industrial regions), the shift to net zero risks stagnation from political resistance from the very workers it disrupts.

Overall, green bonds have indeed demonstrated success in proving that markets can price environmental value without sacrificing financial returns (as evidenced by the “greemium” vanishing). Despite steady progress, more stringent regulation, transparency, and investor scrutiny is needed to turn ethical ambitions into credible, practical financial solutions to tackle the very problem it was designed to help tackle. Going forward, the important test remains whether this $2.7tn market can translate funding into impactful, verifiable CO2 reductions at the necessary speed and scale, making the challenge not about making these bonds bigger, but to make them count.