Regardless of external shocks and continuous structural challenges, the Asia-Pacific region is outpacing its growth expectations. The Director of the IMF’s (International Monetary Fund) Asia and Pacific Department, Krishna Srinivasan, stated, ‘The region is once again set to contribute the lion’s share of global growth: about 60% both this year and in 2026’.

Although this news is very positive, Asia has been growing this decade at a slower rate than the last. As recent news indicates, tariff uncertainty remains unresolved as they could yet still increase. Additional structural headwinds that could affect the region, especially if geopolitical tensions and trade policy uncertainty become worse, include the rising of risk premia and interest rates.

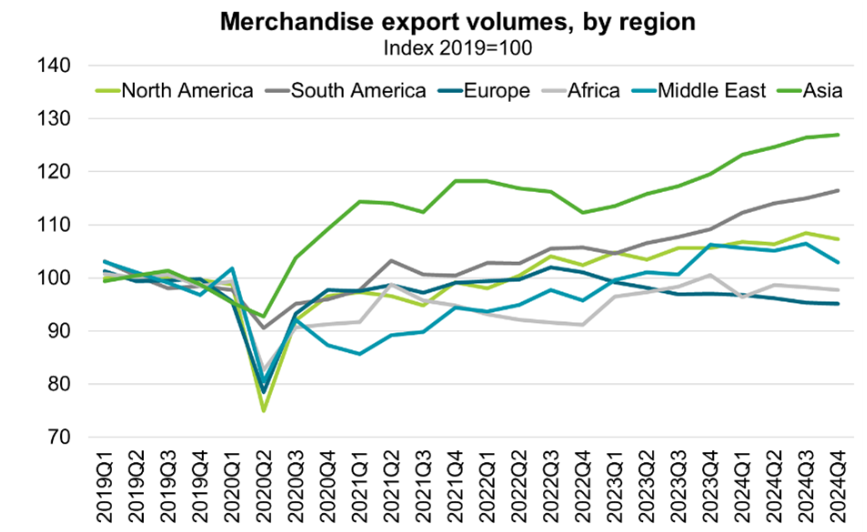

Export Finance Australia noted that Asia’s economies are worryingly dependent on global trade, which makes them more vulnerable if tensions were to rise. For example, Vietnam recorded a trade-to-GDP ratio of approximately 165% in 2023. Essentially, this means the total value of goods and services traded (imports and exports) was around 1.65 times its GDP, making it one of Asia’s most trade-dependent economies. As many countries in the region heavily rely on imported inputs and export-driven growth, slight disruptions, such as tariffs, can ripple quickly through supply chains. So, what once fuelled rapid growth has quickly become a structural weakness, which has ultimately increased exposure to global shocks.

Research on supply-chain reallocation shows how firms are already shifting production due to the threat of these geopolitical risks. Many are beginning to adopt “China + 1” strategies, broadening operations across Vietnam, India, and other Southeast Asian economies. A very good example of this is Apple’s build-out of manufacturing in Chennai, South India. Suppliers like Foxconn and Pegatron are producing millions of iPhones annually. These shifts show how supply-chain restructuring is no longer theoretical, it is officially underway as these firms react to the rising uncertainty.

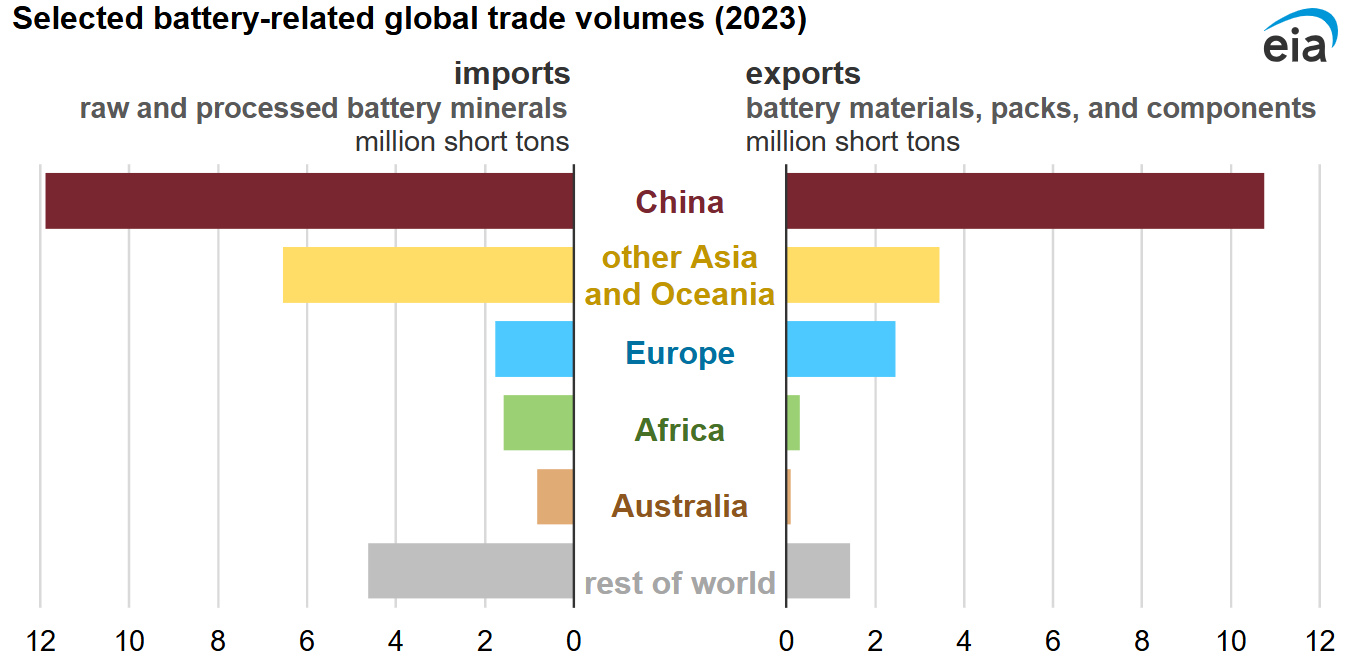

A recent study of rare-earth supply chains indicates how trade risk does not only reduce volumes of trade, but it can also weaken a country’s ability to sustain key industries. This study indicates that when trade tensions rise, the concentration becomes a massive vulnerability as it can suppress comparative advantage and disrupt downstream industries.

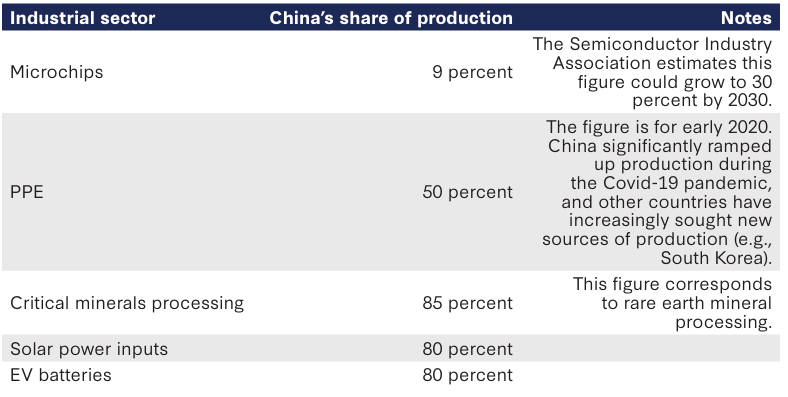

The key sectors which are most exposed to supply-chain risk include critical minerals, semiconductors, and electric vehicles (EVs). The semiconductor industry unfortunately, depends highly on a specialised network of raw materials and processing steps, which are only found in a small number of countries. Furthermore, many EV manufacturers require specific minerals such as lithium and graphite. China is responsible for 90% of the world's natural graphite refining and 65% of lithium. Due to this, any geopolitical disruption could spread outwards and threaten the resilience of technology value chains.

In response to this challenge, many firms are diversifying their supply chains in response to geopolitical risk. According to surveys from the American Chamber of Commerce in China, 10 percentage points more U.S. companies are shifting investment toward Southeast Asia, with Malaysia, Vietnam, and India being popular alternatives. Similarly, the European Chamber of Commerce in China reports that 13% of companies have moved their existing assets out of China and an additional 8% are also considering doing so. These are just 2 examples of how supply-chain realignments are no longer hypothetical; they are already underway.

Governments are encouraging “friend-shoring” through financial incentives. A recent program launched in Japan, through METI (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), has subsidised 220 billion Japanese yen for countries to reshore to Japan or shift production to a friendly country is Southeast Asia as part of their supply-chain diversification strategy.

Additionally, other countries in the Indo-Pacific region are introducing similar measures. For example, The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy in South Korea is set to provide ₩9.7 trillion (roughly $7.1 billion) in state financing to the EV-battery sector, which also includes tax incentives and low-interest loans. This is to encourage the relocation of strategic production to reduce dependence on a singular production hub and strengthen supply-chain resilience.

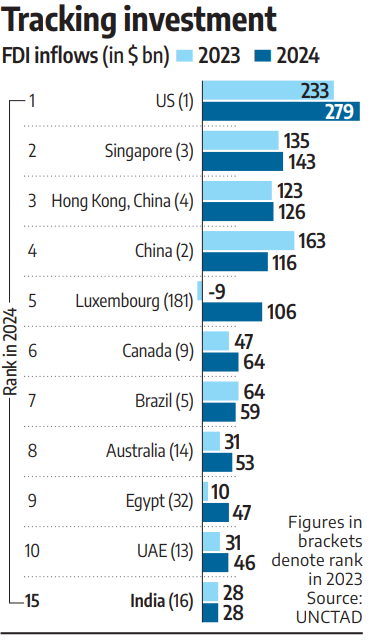

The biggest winners from all this supply-chain realignment have been ASEAN and India. Data shows that FDI inflows into ASEAN countries hit a record of $230 billion in 2023, indicating that countries around the world are no longer just treating this region as a low-cost alternative, and instead are starting to see it as a core production base.

In fact, this investment is predominantly flowing into green tech, manufacturing, and electronics, all of which previously leaned heavily toward China. Furthermore, India also saw $28 billion in FDI in 2023, making it a global top 15 FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) destination, which reflects investor confidence in its government-backed incentives and growth potential. These trends show us how these regions are gaining a great share of redirected global investment.

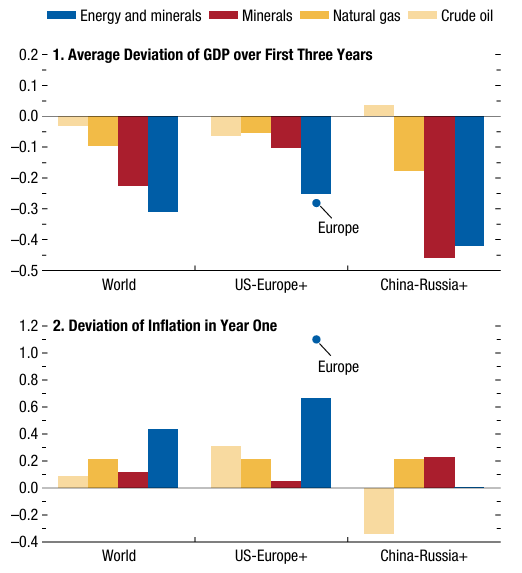

When it comes to the scale of the economic risks related to global trade fragmentation, the IMF provides a clear representation of this. Data shows that global GDP could fall by anywhere between 2-7% if the world fractionates into these different trading blocks, which will ultimately end up competing. How drastic the fragmentation becomes will determine how harsh the effect on GDP will be.

Due to the fact that Asia is the world's most trade-dependent and globally integrated region, many believe that it will be disproportionately affected by this fragmentation compared to other regions, as a lot of Asian countries rely immensely on cross-border supply-chains for both demand and production. What the IMF is warning us of is that the disruption of these networks would lead to decreased efficiency, making it much more difficult for Asian firms to access key resources.

The reason why geoeconomic fragmentation is so costly is that is decreases efficiency across production networks. Research from the World Bank and OECD supports this. The OECD found that when countries pull out of global value chains, productivity in countries which are highly open can fall by approximately 5% and this is mainly due to factors relating to the loss of large markets and specialised suppliers. Additionally, the World Bank indicates that shifting production to new regions may potentially increase the price of machinery and electronics by between 10 to 12%. In some scenarios, more intensive decoupling could raise these costs up by 20% in some more vulnerable industries.

Research at the firm-level shows that the costs of fragmentation directly impact business operations. The Peterson Institution for International Economics (PIIE) found that policies such as tariffs and export controls have the ability to increase production costs as companies are forced to source from less efficient suppliers. These disruptions also affect consumers as the increased costs are passed down the chain. McKinsey adds to this by emphasising how the reconfiguration of global supply-chains to avoid geopolitical risk could cost up to $1 trillion in new investment worldwide.

On the contrary, the CSIS and IISS have shown why some governments still believe friend-shoring will give their nation a strategic benefit. Through decreasing reliance on politically risky suppliers, especially in sectors like semiconductors and minerals, CISI shows how this can drastically strengthen national security by lowering the risk of factors such as export controls. Additionally, IISS suggests that shifting supply chains towards more trusted partners can strengthen alliances and decrease vulnerability to trade measures. Through this perspective, the higher economic costs of friend-shoring can be justified as they bring geopolitical stability and resilience.

To tie this analysis back to the Asia-Pacific, this region faces a particularly harsh version of the trade-off. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) suggests that if global fragmentation were to deepen, it could reduce Asia’s long-term output by around 3.3% (reflecting the regional dependence on cross-border relationships). However, the ADB also identifies that diversification towards more trusted partners can also have its benefits, such as creating more predictable long-term supply relationships and reducing exposure to geopolitical shocks. This highlights the dilemma Asia finds itself in: fragmentation carries potentially detrimental economic costs, but diversified supply chains can build strong alliances and improve strategic resilience.

Asia-Pacific is now entering a phase where it lies at the intersection of economics and geopolitics. How the region grows and trades is being reshaped by friend-shoring and supply-chain realignment. Fragmentation can carry economic costs like lower productivity, but diversity can bring strategic security, especially in sensitive sectors like semiconductors.

The biggest challenge this region faces is choosing the right balance between growth and security, because leaning too far into growth increases exposure to external shocks, while prioritizing only security can slow development. The countries that will come out on top of this fragmentation are those that can balance this trade-off the best. These countries will shape the economic trajectory of Asia.