• Importance of data flow: US economic calendars rely on timely government releases, making each update essential for investors.

• Impact of the shutdown: With federal agencies offline, markets were forced to lean on private-sector datasets instead.|• Limits of private data: Alternative data can offer useful signals, but it lacks the reliability, coverage, and consistency of official government statistics.

• Limits of private data: Alternative data can offer useful signals, but it lacks the reliability, coverage, and consistency of official government statistics.

I’ve finally managed to book my driving test, thanks to a 5:45am wake-up. As in the world of financial markets, “the early bird catches the worm”.

My main source of learning has been driving lessons and picking up on the good (and bad) of driving from my parents and friends. I did not expect to be taught about driving from the venerable, sensible Jay Powell, the chair of the US Federal Reserve.

“What do you do when you’re driving in the fog? You slow down.”

Albeit a useful reminder, the fog that Powell and his team, Federal Open Market Committee, have been facing is far worse than the one I might face in the driving seat.

The latest US government shutdown paused the official data collection and publication. Agencies including the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) were frozen through the 43 days, unable to do their constant pivotal work in gathering statistics for the economic world to understand.

Markets started looking elsewhere, namely at private data. The question we now ask is whether this private data is reliable and should we use it more in the months and years to come.

The world cares a lot about what happens in the world’s largest economy. We take our measurements of how it’s doing mainly from 2 sources: its economic objective performance and the Fed’s interest rate.

Of course, they work hand-in-glove: the Fed’s decisions follow from GDP or CPI data, which are, in turn, impacted by the changes in interest rates.

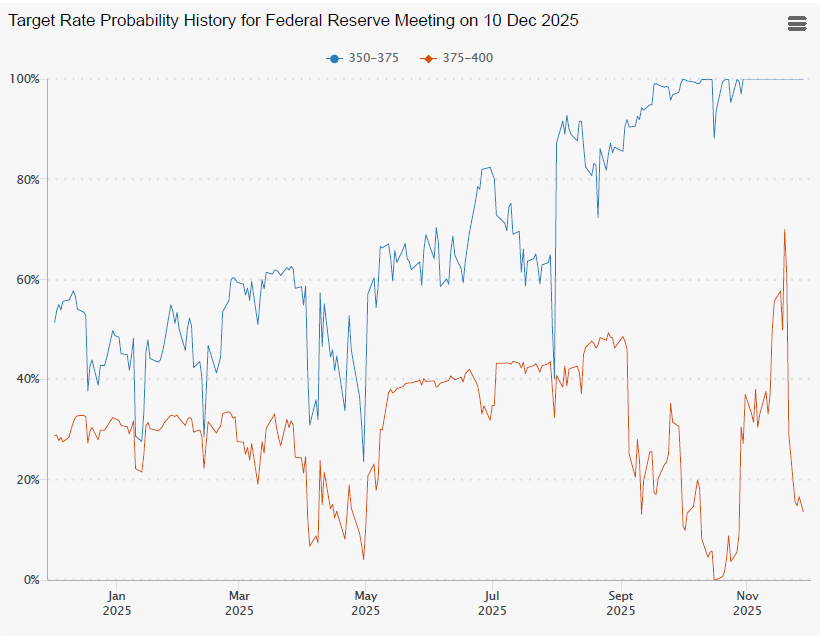

Hence, firstly, this gap in economic data - specifically, CPI and real-time unemployment data - hampers the Fed as it prepares for the December decision on the 10th. This builds on an increasingly volatile and divided expectation, with the CME FedWatch tool, representing sentiments around rate cuts, painting a clear picture.

It also has real-world impacts: the FT mentions that “Any hole in the data series will have potential ramifications for everything from social security payments that are pegged to inflation numbers to businesses making hiring and inventory decisions ahead of the holiday season”. For businesses, the uncertainty continues to ratchet up, on top of discontinuous trade policy and shaky consumer spending.

The weight placed on these US economic figures means their announcement rings through global markets, across asset classes. The S&P 500 can swing within minutes, emerging market central banks adjust their policies and US Treasury bills are impacted too. And beyond the short term, they impact medium term decisions that are informed by expected growth and capital investment figures. Hence, the shutdown-induced AWOL meant looking for substitutes.

Fundamentally, market operations had to continue. Asset managers, traders, hedge funds needed to find a way to make sense of the muddy waters, still seeking to make a return for their clients.

They had to get creative and they turned to a variety of sources. The payrolls processor, ADP became the most quoted figure during the period. They have a monthly estimate of employment growth on its own data.

RSM outlines that changes in the number of paychecks processed by ADP appear to conform to the BLS’ final revised version of private (nongovernment) nonfarm payrolls - from 2022, the correlation coefficient between these two numbers is a healthy 0.79. However, unlike the survey-based data of the BLS, the ADP figure is based on hard data, namely the number of paychecks actually processed each month.

Other sources included Challenger, Grey and Christmas, a global outplacement and executive coaching firm, who measure the number of job cuts announced by employers. The jobs platform Indeed can provide data on job openings and, more interestingly, the evolution of different types of jobs. Finally, Revelio Labs is a workforce intelligence platform, using employee data from networks like LinkedIn and websites to spot patterns in the labour markets. Their real-time analytics often means they can pick up on trends in particular industries well before official statistics.

This raises the question, “what’s the point of public data? Can we just work with private data?” Let’s investigate.

As is the advantage from the private market in other markets, we gain speed. Private sector data can be collected more in real time and this shorter lag can help inform policymakers. This article highlights the trends you can spot from looking at private data, including the labour market’s crash and recovery during the pandemic as well as housing market behaviour around the GFC.

Furthermore, they are able to provide more categories and classification at scale - companies can quickly use their data to generate insights that are specific to a sector, geography or demographic group. Federal surveys do not usually have that level of detail in order to reliably break them down like this. A long-term global trend in data collection is a decline in response rates, testing the reliability of public data. You could argue that private data will soon allow for far bigger volume advantages.

Together, we can argue that private firms are able to capture niche economic trends faster, ultimately allowing decision makers to diagnose problems earlier.

And overall, as this piece from the FT highlights, they aren’t that far off.

.png)

The simple microeconomic concept of incentives plays out here. Private firms are not collecting this data with the pure intention of informing the public and shaping effective policies.

Instead, their approaches are - as you would expect - self-interested. In protecting themselves from liability and unfavourable optics, as well as reserving any material trading secrets and insights they have gained, their data may not capture the whole picture.

To zoom in on the US situation, it is wise to note that firms are exceedingly keen to be on President Trump’s good side. His August firing of the Bureau of Labour Statistics’ commissioner Erika McEntarfer, claiming a downbeat announcement “rigged”, is another disincentive to truthful reporting.

Furthermore, a question of quality control is paramount. Given the importance and sensitivity of the news ensuing from this data and the subsequent investment and policy decisions that are taken, we should be able to critique the methods used to produce it. Sadly, private data is fundamentally not as rigorous as the carefully produced government data. The private sector will not agree to be subjected to the same levels of confidentiality, public scrutiny or transparency that we demand of the BLS.

For example, the polling firm Morning Consult has a regular unemployment index; however, a pop-up window on their website mentions that the tracker is only “temporarily available for free” and its methodology is only explained behind a paywall. This raises the question of whether economic data is a public good, or should be reserved for those who can pay for it? Having to pay for high quality data creates a disparity between the big players who have the resource heft to pay and smaller players, ultimately reducing the efficiency of the stock market.

One interesting point that goes against private sector entrepreneurialism is its ability to innovate. The fact that “history doesn’t repeat but it rhymes” invites us to make long-run historical comparisons, to observe and learn from economic cycles. Hence, the consistency behind the public sector methodologies enable us to make safe and accurate long-run comparisons.

Speaking of comparing, the lack of standardisation in private data makes it hard to use in the round. Official statistics are designed to be representative and cover the entire population. However, private sources don’t have the entire picture. In contrast, companies only see their users or customers. Credit card data miss the unbanked. Additionally, private data is poor at judging services inflation, which forms a sizable 64% of the CPI basket and creates a gaping blind spot.

Finally, these private sources are themselves influenced by the public data sources. The ADP uses the BLS’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) to develop representative weights for its source data. This means that the ADP data couldn’t completely replace our trusted BLS.

As any good economist will tell you, it is a ‘combination of policies’ that will work. It is clear that there are merits in observing private data and perhaps investors and researchers will now spend more time examining their more unique, bespoke releases, searching for a point of difference or a time advantage.

One policy suggestion currently being evaluated is setting up an opt-in between businesses and Census Bureau, to share digital data and hence removing the need for manual, time-consuming survey responses. This is an encouraging idea, playing on the ideas of Richard Thaler and nudge economics.

A main hurdle will be trust: in a world where we have ICE wanting to access IRS taxpayer data and insurance claims data, any hope of making private data more usable will only come with consumer confidence that data will be kept confidential and not misused.

However, it is clear that the BLS and the data it produces continues to be invaluable and paramount. This makes the threats it faces, from politicians and from persistent budgetary constraints, alarming and makes us question whether we will be able to trust even public data in the future.